ISTIJRAR: A PRODUCT OF ISLAMIC FINANCIAL ENGINEERING

MOHAMMED OBAIDULLAH

Islamic scholars and economists are involved in a continuous process of designing and developing new financial instruments and finding innovative solutions to financial problems in the Islamic framework. Islam imposes two important constraints that distinguish Islamic financial engineering fi-om the conventional one. Islamic financial products must be free from Riba and Gharar.

In conventional parlance, this implies that such financial contracts must avoid conditions of zero risk and also conditions of uncertainty. These are two extremes in a continuum of risk. Unfortunately, however, these are present in most of the traditional financial engineering products and involve either risk-free returns or returns through speculation under conditions of uncertainty. Both are considered unethical and not permissible from the Islamic point of view.

A problem that confronts every participant in various markets, such as the commodity, securities, and currency markets, relates to management of risk arising out of volatility in prices. Th e need to manage risk has led to the development of various hedging tools that involve the use of options, futures, swaps and other derivative contracts.

However, most of these tools of risk management can also be used for speculation and arbitrage. And, although the need to reduce risk exists for an Islamic organisation or individual participating in the markets, the conventional solutions are not Islamically permissible.

It may be noted here that risk reduction is very much in conformity with Islamic rationality; though an Islamic participant would not seek to reduce risk to zero, the challenge before Islamic scholars is to develop new instruments for risk reduction which avoid the two extremes of Riba and Gharar.

Istijrar is a product of Islamic financial engineering. It has been recently introduced by the Muslim Commercial Bank in Pakistan and is being used for commodity financing. T h e purpose of this paper is to undertake an anatomy of this financial innovation.

In part 1, we examine its various features. We also discuss some issues relating to the Islamic nature of Istijrar and undertake a comparison with some similar products of conventional financial engineering.

In part 2, we mathematically derive conditions to be considered while structuring the deal which make the contract more just and equitable. In part 3, we conclude and make a case for the use of Istijrar as it adds to the efficiency of an Islamic financial system.

1. Features of Istijrar

a) The Contract

Istijrar involves trade. According to the Istijrar contract, the sale price of the commodity that is traded is computed as the average of the market prices during the financing period.

The contract also has embedded options for both the buyer and seller that are activated if the market price pierces an upper or lower boundary during the financing period. The option provides a right to a party to fix the sale price at a predetermined level.

To elaborate, let’s take the example of a firm requiring short-term financing of its raw material purchases for a specific time period – say, six months. The firm approaches an Islamic bank for financing this purchase. The bank purchases the pre-specified materials and sells these to the firm. The sale price, unlike a simple trade, is not set at the time of entering into the contract. Rather, it is determined at the end of the financing period, that is, six months. The sale price is set as the average of the series of prices of the material during the period of six months. Both the firm and the bank agree on a public undisputed source of price information and also a sampling interval for observing prices. Th e average price is calculated from these observations.

The contract has embedded options for both the firm and the bank to fix the sale price at a different, predetermined level. These options may be activated if prices fluctuate too much and cross either a pre-specified upper or lower bound. The buyer-firm has an option to fix the sale price provided the market price exceeds the upper boundary at any time during the financing period. The bank also has a similar option if the price falls below the lower boundary. The option is to fix a sale price at a pre-determined level payable on the due date.

b) Issues Relating to Al-Riba and Al-Gharar

Istijrar involves trade and hence does not involve any possibility of a risk-free return by either party. A real transaction involving purchase, ownership and sale of a commodity underlies financing through Istijrar. The bank is exposed to risk and hence, Istijrar is clearly free from Riba.

Possible arguments against Istijrar may, however, be on the grounds that the bank or seller is exposed to too much risk. The risk in this case is price risk. Islamic law provides for stipulation of the price at which the deal is executed in the contract. Absence of the price in the contract would involve Gharar or uncertainty.

It may be argued that a simple alternative for the bank is to finance the same transaction under Murabaha, that is, charge a predetermined profit above the purchase price and sell it at the cost-plus price on a deferred payment basis. Since the payment to be made to the bank is known with certainty, there is obviously no element of Gharar.

This arrangement reduces price risk to zero and minimises overall risk for the bank, which is reasonably certain about the return on its investment. However, this alternative is the least preferred form of financing from the Islamic point of view, and, according to some Islamic scholars, is very close to Riba-based transactions. Hence, its use should be minimised. The goal of risk minimisation should not imply seeking predetermined returns as in the case of debt financing.

The amount of risk associated with Istijrar is not as high as it appears initially. Price risk would of course become prohibitive when the contract provides for setting the sale price at the level prevailing on the maturity date.

In a market where prices are not administered and are freely determined by market forces (as would be the case in an Islamic market), such a contract would involve conditions of uncertainty or Gharar. Istijrar, on the other hand, provides for a process of averaging of the prices prevailing during the financing period, which reduces this uncertainty to a considerable extent.

The element of uncertainty is further reduced by the options which are activated when market prices become too volatile and cross the price band from either side. When the options are exercised, the outcome is similar to that under Murabaha, that is, the sale price is fixed at a level which allows for a predetermined profit to the seller.

c) Istijrar and the Statistical Properties of Price Behaviour

In statistical parlance, conditions of risk are distinct from conditions of uncertainty. Conditions of risk refer to a situation where it is possible to enumerate the entire range of possible values that the variable in question (commodity price) may take, and the corresponding probabilities.

In other words, it is possible to estimate the ex-ante probability distribution. Such estimation is usually undertaken on the basis of the historical relative frequency distribution. No such estimation is possible under conditions of uncertainty. We use this distinction in our analysis and label the latter type of situation as involving Gharar.

The beauty of Istijrar lies in its ability to cope with various alternative sets of assumptions regarding behaviour of prices. An assumption quite common among economists is that prices fluctuate randomly. The assumption is that prices are not administered; they are freely determined by the forces of demand and supply and are free from any market manipulation.

In such a case, distribution of prices could be approximated by a normal distribution. A desirable statistical property of the normal distribution is that the entire distribution can be described by just two parameters – mean and standard deviation.

If the prices of the commodity in question are devoid of manipulative trends and fluctuate freely and randomly, then the analytical framework becomes quite simple. Prices would centre around the mean of the distribution, that is, the average of all prices during the financing period.

The upper and lower bounds for the prices are given by another property of the normal distribution: 99.7 percent of all prices would fall within (mean + 3 standard deviations) to (mean – 3 standard deviations). These bounds would effectively take care of all possible prices. The mean of the distribution of prices however may shift to the right if prices exhibit a long-term upward trend.

If this shift in mean can also be estimated, then structuring the contract becomes quite simple. The exercise price for the options could be set after taking into consideration the rightward shift in the mean. Under these conditions, the outcome would become independent of whether or not options were activated (this makes the bounds irrelevant) and whether or not options were exercised. The sale price is eventually set at a level that almost allows for a pre-determined profit for the seller.

It may be noted that if the sale price is set at the level prevailing on the maturity date, this would imply any of the possible values that the price might assume. Even if the probability distribution of the price is stable, the price at which the deal would be closed, and the payment to be made, would be shrouded with uncertainty and hence, the arrangement would not be free from Gharar.

However, if payment is set at the mean of the probability distribution, which can be estimated, the situation can no longer be termed as uncertain. The Istijrar contract in this scenario would involve a risk that is Islamically permissible and not uncertainty or Gharar.

The Istijrar contract also has built-in features to cope with conditions of uncertainty, where the probability distribution of prices cannot be estimated and historical distributions provide little clue to ex-ante distributions.

If prices exhibit unexpected trends, then the mean of the expected distribution would be non-stationary. It would be continuously shifting in either direction and setting the sale price at the mean of all past prices would involve a high degree of uncertainty. This situation is thought to be taken care of by having options which would be activated and exercised in case of extreme adverse movement in prices, and the sale price would thus be settled at a predetermined level which would allow a known profit as in the case of a Murabaha contract.

d) Comparison with Certain Traditional Financial Innovations

Istijrar is a complex instrument that has some similarities with certain traditional financial engineering products, such as the average rate (Asian) option, the barrier option, and range forward contracts. All these financial innovations pertain to transactions in currencies, although they could also be used for commodity or stock transactions.

The average rate (Asian) option is a contract that pays off, at option maturity, the difference between the option strike price, say P*, and the average price, say P-bar, over the life of the option.

Barrier options are of several types. But the ones similar to Istijrar are down-and-in options and up-and-in options. In a down-and-in option, the option feature is activated only if some lower barrier is crossed prior to option expiration. In an up-and-in option, the option feature is activated only if some upper barrier is crossed prior to option expiration. The Istijrar contract combines the features of an average rate (Asian) option, a down-and-in put, and an up-and-in call.

There is some difference of opinion among experts in Islamic law about the permissibility of option contracts. The majority view seems to be that such option contracts in themselves are permissible and are normally binding on the party which is obligated under the contract.

However, this contract cannot be a subject matter of sale and purchase implying that no premium can be charged by the option writer. The rights and obligations cannot be transferred to a third party.

It is not difficult to see the economic significance of this requirement. If the option contract is made fully transferable it brings in the possibility of speculation on the direction of price movement. For example, consider the case of an up-and-in call on the price of a specific commodity with an upward barrier at P-cap and exercise price P* (P-cap naturally is greater than P*).

If an individual expects prices to cross P-cap before the maturity date and remain above P* on the maturity date, he would buy this contract. If his expectation materialises, his gain would equal the difference between the price prevailing on the maturity date and the exercise price minus the call premium.

His losses are, however, limited to the call premium in case his expectation does not materialise, and the option expires worthless. Such a scenario is likely to encourage individuals to speculate and benefit from the price differences. Such speculative gains are against the norms of Islamic ethics.

Istijrar, however, does not allow any room for controversy or difference of opinion, as the options are embedded in the contract and are not tradable in themselves. The contract does not allow for any kind of speculative gain, as it is backed by a real purchase, ownership and sale of a commodity.

Istijrar can also be compared with another financial innovation: the range forward. This is a simple extension of a forward contract and can also be seen as a combination of a call and put option. In a range foward, there is no single forward price as in a simple forward contract. Rather, there is a “range” for the forward price.

In the context of commodity transactions, a contract may, for instance, stipulate that the buyer will buy the given commodity from the seller at a price ranging from PI to Pu. This also implies that, independent of the spot price, the buyer has the right to buy from the seller at ceiling price Pu (seller has the corresponding obligation to sell at Pu) and the seller has the right to sell to the buyer at floor price PI (buyer has the corresponding obligation to buy at PI).

Thus, similar to a simple forward contract, both the parties have rights and obligations to transact. The difference is that the rights and obligations to transact are not at a unique forward price, but at different forward prices.

Range forward, like the simple forward contract, is not Islamically permissible, primarily because it allows both the parties to make speculative profits from price differences and is essentially a zero-sum game. For example, if on maturity, the spot price happens to be above Pu, say Ps, then the buyer would make a profit of Ps-Pu by exercising his right to buy at Pu. The loss to the seller would be the same. The converse would be the case if, on maturity, the spot price falls below PI.

The possibility of speculation, however, is reduced as compared to a simple forward contract where there is a single forward price for both the buyer and seller. In case the spot price remains within the band, then both the options expire without being exercised.

Istijrar, like a range forward contract, also has a combination of a call option and a put option. However, unlike a range forward contract, the buyer and seller are not in a position to speculate on the direction of prices and take the price differences. It is this constraint on speculation that distinguishes Istijrar from traditional financial engineering products and makes it conform to the norms of Islamic ethics.

2. Analysis of Embedded Options

Let us consider the case of an option for the buyer first. The buyer-firm would exercise the option to fix the sale price if it expects the price increase (after it has risen above the upper bound) to continue. Let FBI, PB2, PB3….PBn be the expected price series for the buyer. The option would be exercisable in time period t if PBt is greater than the upper bound, say P-cap.

If the buyer exercises the option, the sale price would be fixed at a predetermined level P*. Whether the option would be exercised depends on the nature of change in the buyer’s expectations. If the buyer expects that beyond time period t, prices will keep moving up, which would imply that the average of the prices during the entire time period would be driven up and would be higher than P*, then the buyer will be better off by exercising the option.

However, if the buyer expects that prices will fluctuate randomly, and the increasing trend in prices will not persist, then he will be better off by not exercising the option. The condition for exercising the option is the Expected Value of the price distribution PB-bar > P*. If P* is not too high, then the buyer-firm would be more inclined to exercise its option since the probability of the average of prices being greater than P* would be high. However, if P* is set at a high level, the existence of the option is not likely to confer much benefit on the buyer.

Now let us see what would happen if prices fell below the lower bound. The bank would exercise the option to fix payment at the predetermined level if it expected the price decline (after it has fallen below the lower bound) to continue.

Again, let PSI, PS2, PS3….PSn be the expected price series for the seller-bank. The option would be exercisable in time period t if PSt were lower than the lower bound, say P-floor. If the bank exercises the option, the sale price would be fixed at the pre-determined level P*.

Whether the option would be exercised depends again on the nature of change in the bank’s expectations. If the bank expects that beyond time period t, prices will keep going down, which would imply that the average of the prices during the entire time period would be driven down and would be lower than P*, then the bank will be better off by exercising the option.

However, if the bank expects that price decline is purely temporary, then it would in all likelihood, be better off by not exercising the option. The decision would depend on the value of P*. If the bank manages to fix P* at a sufficiently high level, so that the average of prices would eventually be less than P* then the bank would exercise the option the moment the price fell below the lower limit.

What follows from the above analysis is that the level of the predetermined price P* is a crucial parameter of the contract. Given the expected distribution of prices, P* will determine whether the options will be exercised by any party.

Generally, P* would be dependent on the market price prevailing at time period zero, that is, the price at which the commodity in question is purchased by the bank for delivery to the buyer. P* is expected to be the bank’s purchase price plus a minimum predetermined return, as in case of a Murabaha contract. Using notations, if Po is the purchase price and r is the predetermined return, then P* = Po (1+r).

The other crucial decision variables in designing the contract are the upper bound Pcap and the lower bound P-floor, as these have wide implications for the buyer and the seller. The level of P-cap determines whether and when the buyer will have the option. If P-floor is fixed at a fairly high level, and the price fluctuates in a narrow range, then the buyer will not be in a position to exercise the option and hedge against moderate price increases. It would be in the interest of the buyer and against that of the seller to fix the upper limit at a low level.

The situation is symmetrical for the lower limit P-floor. If the P-floor is fixed at a fairly low level, then the seller will not be in a position to hedge against moderate price declines. He will not have any option if the price fluctuates in a narrow band and does not pierce the low P-floor. It is, therefore, in the interest of the seller and against that of the buyer to fix the P-floor as high as possible.

Setting the values of P-cap and P-floor thus involve a conflict of interest. It is quite easy to conclude that the decision would be dependent upon the relative bargaining power of the buyer-firm and the seller-bank.

In the interest of equity, however, the buyer and seller must share the risk in a just manner and no single party should be in a position to tilt the balance in its favour. In other words, the value of the option for the buyer must equal the value of the option for the seller at the time of entering into the contract. For every P-floor, it is possible to derive a P-cap where this equality holds good.

a) Equality in Option Values

As already pointed out, the option to the buyer is in the nature of an up-and-in call and the option to the seller is in the nature of a down-and-in put. Further the options are in the nature of average rate (Asian) options. The value of these options to both the parties must be equal.

We arrive at the condition for equality using the standard valuation approach suggested by Cox, Ross and Rubinstein (1979), that assumes that the underlying price follows a multiplicative binomial process.

Here it may be noted that the traditional models attempt to compute the value of an option with the objective that the option will be priced accordingly in the market. We have no such objective and hence, the exercise does not violate the Islamic norm that options should not be priced and be the subject of sale.

Our only objective is that the worth of the options granted to both the parties should be the same and we use the valuation models for this purpose alone.

The parameters that determine the value of a barrier option are as follows. For an up-and-in call, its value is directly related to the current market price. The higher the current market price, the greater is the probability that the price will cross the upper bound and will remain above the exercise price on the due date.

For the same reasons, the value of the up-and-in call is also inversely related to the exercise price, and also to the upper bound. The case for a down-and-in put would be the opposite. Its value would be inversely related to the current market price and would be directly related to the lower bound. The other parameter which one finds in the conventional models is the interest rate. However, since we are assuming an Islamic financial system, interest rates would either cease to exist or would have no impact on option values for an Islamic investor.

Lastly, volatility also has a direct impact on all option values. It may be noted that since we are considering the case of average rate options, the volatility measure needs further adjustment. The exact relationship between the volatility of an ordinary European option and that of the average rate option depends upon the frequency with which price observations are collected for averaging.

If the average is calculated from daily observations, the volatility of the average rate option is 57.85 per cent of the corresponding European option volatility. This can be easily derived as follows.

In the case of the European option, the price variable is always a stochastic variable, while in the case of the average rate option, a larger and larger part of the variable (average price) becomes non-stochastic as time passes. Let P be the random price variable and s2 be the annual variance. The variance for the first day is s2(l/365), same as for the European option, as the variable is the same for both the options.

At the end of the first day, the price will be observed and this will serve as the first point to calculate the average. On the second day, the random variable for average the rate option is no longer P, but (364/365) P with a variance of (364/365)2s2(1/365). The daily variance will continue to decline and on the last day will be (l/365)2s2(1/365). Averaging all the daily variances and comparison with the daily variance for the corresponding European option yields the above result.

Apart from the volatility effect, the averaging process introduces an interest rate effect, which is irrelevant in our framework. Hence, once the averaging effect is captured in the volatility measure, the modified measure is taken into account in the model to value the barrier options.

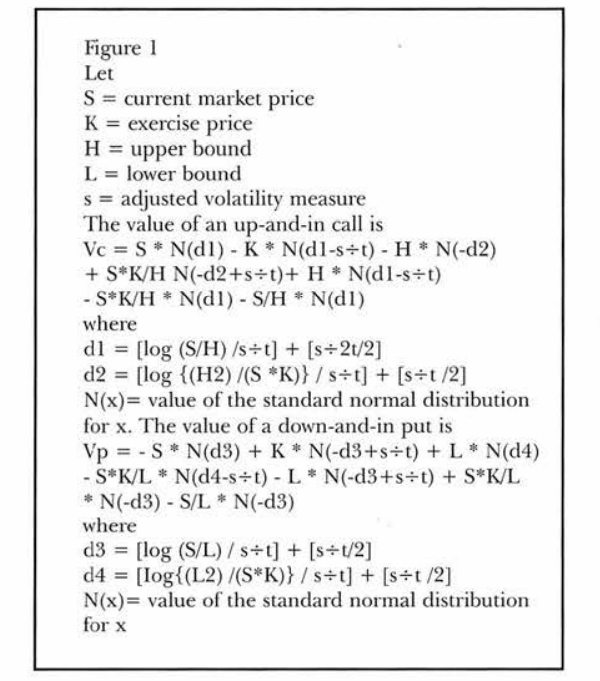

We also assume that the upper bound is higher than the exercise price, which is again higher than the lower bound. J Orlin Grabbe (1996) follows the Cox, Ross and Rubinstein approach and provides the C code for numerical pricing of barrier options. Decoding the same and assuming a zero-interest rate, we find the value for an up-and-in call and a down-and-in put. The assumption of a zero-interest rate greatly simplifies the model. We use the following notations, as shown in figure 1:

As discussed earlier, Vc and Vp must be equal in the interest of equity and justice. To take an example, we initially assume that the current market price (S) is 100, the exercise price (K) is 120, the upper bound (H) is 150, the lower bound (L) is 90 and the volatility measure is 0.25.

Given this, we compute Vc to be 6.567 and Vp to be 21.63. Thus, there is a wide disparity between the option values and the contract is tilted in favor of the seller-bank. When the upper bound is reduced to 125, Vc rises to 11.962, and the disparity is reduced. Similarly, when the lower bound is reduced to 75, Vp

decreases to 12.691 and is equal to Vc when the lower bound is further reduced to 74 approximately.

When the deal is structured by the seller bank, it may prefer to fix the lower bound for itself taking into account the price risk it is willing to bear. As noted earlier, the higher the lower bound, the lower is the price risk. And the higher the lower bound, the higher would be Vp. The equality condition would demand that Vc is also higher.

Vc would be higher, given the values of other parameters, only when the upper bound is lower. Consequently, the price risk to the buyer-firm would also be lower. For every value of the lower bound, there would be a corresponding upper bound where equity is ensured.

3. Concluding Remarks

As already noted, traditional risk management tools using derivatives, such as options, forwards and futures, are not permissible in the Islamic framework, primarily because these are also vulnerable to misuse by speculators.

Speculation and arbitrage, and not risk management, seems to be the more dominant motive behind entering into the above contracts in contemporary markets in commodities, stocks and currencies.

Nevertheless, the excessive volatility witnessed in these markets underscores the need to design tools for risk management without violating the requirements of Islamic law. As already highlighted, Istijrar, which is now being used for commodity financing, is an Islamically permissible tool for managing the price risk of commodities. There is no reason why this contract cannot be used in other markets for risk management.

Consider the following case. An Islamic equity fund is planning to launch a new scheme after three months. The funds will be available after this time period. The fund manager believes that the current equity prices are quite attractive and that prices are likely to be higher at the end of three months.

A conventional fund manager has the alternative to enter into a future contract to buy the stocks he wants at the end of three months at specific prices; or to buy call options on the stocks with specific exercise prices.

The Islamic fund manager may not like to use these alternatives. Bai-Muajjal may be an Islamic alternative under which the fund manager takes delivery of the stocks at present against a promise to pay the sale price after three months. The transactions are executed at known prices.

This kind of transaction is feasible only when there is a willing seller with exactly opposite expectations regarding the direction of prices. However, since the seller can always liquidate his holdings now in the spot market and take the sale price, there is no reason why he would choose to wait for three months.

In order to induce him to wait, the price at which the Bai-Muajjal contract is executed must be higher than the current spot price. Under this arrangement, the fund manager is able to hedge the price risk and transfer it completely to the seller, who would have a notional loss if prices subsequently go up.

Istijrar offers another alternative under which the fund manager and the seller are able to share the price risk. As already explained, under this arrangement, risk arising due to moderate price movements within the barriers remains with the parties to the contract (though it is further reduced owing to the process of averaging). Both the parties have a hedged position relating to price movements beyond the barriers.

The contract thus provides a variety of risk management possibilities. The above is just one possible case where Istijrar can be used. The challenge before the Islamic financial researcher is to explore additional uses of this elegant financial contract so as to design new innovative contracts with varying features conforming to the Islamic norms. Thus it would be possible to enhance the efficiency of the financial system without compromising the norms of Islamic financial ethics.

Edited By Asma Siddiqi

Institute Of Islamic Banking And Insurance London

Comments

John Doe

23/3/2019Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

John Doe

23/3/2019Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

John Doe

23/3/2019Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.