CHAPTER 4: THE ISLAMIC LAW OF INHERITANCE

Introduction

In the previous chapter, we presented texts from the Quran and authentic Sunnah that provide the basis for deriving the rules of the law of inheritance. In this chapter, we only present the rules and guidelines, without much reference to the texts, as we feel that we have provided sufficient explanation in their regard.

This chapter concisely covers the major aspects of the law of inheritance. We employ tables and diagrams to reduce space and present the material in a manner that should be more comprehensible to the readers.

Despite the fact that slavery does not exist in our time, we have elected to include slavery-related issues in our discussion of the law of inheritance. This has several reasons; most importantly for the sake of completeness, and to enable the reader to understand some issues related to that when he comes across them in the Islamic literature.

We have followed many of the concepts by illustrative examples to clarify them. However, we have reserved the next chapter for extensive examples and case studies.

Warning Concerning Weak Reports

Books on the subject of inheritance commonly start with a citation of a number of hadiths expressing the importance of this subject. There is no doubt as to the great importance of the subject, because it sets a clear methodology for passing down the worldly wealth from predecessors to successors. Because of this, we saw in the previous chapter that Allah (swt) has rationalized it in His Book and in the Sunnah of His Messenger (pbuh).

However, it is important to note that the commonly cited hadiths are weak and should be avoided. This refers in particular to the following:

1) The report from ‘Abdullah Bin ‘Amr that the Prophet (pbuh) said, “Knowledge is of three types, and anything beyond that is unnecessary: a clear ayah, an established sunnah, or a just rule (of inheritance).” (Recorded by Abu Dawud and Ibn Majah. Verified to be weak by al-Albanl (Daif ul-Jami no. 3871).)

2) The report from Abu Hurayrah that the Prophet (pbuh) said, “Learn the Quran and the rules of inheritance, and teach them to the people, because I will surely be taken away (by death).” (Recorded by at-Tirmidhi and Ibn Majah. Verified to be weak by al-Albanl (Daif ul- Jami no. 2450).)

3) The report from ‘Abdullah Bin Mas’ud that the Prophet (pbuh) said, “Learn the knowledge and teach it to the people; learn the rules of inheritance and teach them to the people; learn the Quran and teach it to the people. Verily, I will be taken away (by death), the knowledge will be taken away, and tribulations will become paramount — so that when two people differ about a rule of inheritance they will not find anyone to arbitrate between them.” (Recorded by ad-Darimi and others. Verified to be weak by al-Albani (Irwa‘ ul- Ghalil no. 1664).)

Definitions

ILM UL-FARA’ID

The Islamic law of inheritance is called ‘ilm ul-fara id, or “the subject of the injunctions (concerning inheritance)”. It involves knowing the rules for dividing the inheritance and distributing it so that each of the heirs receives his proper share.

Difference in Understanding

It is important to realize that, like any other knowledge or specialty, the scholars vary in their understanding of this subject. Even the sahabah varied in this regard, and the Prophet (pbuh) indicated that the most knowledgeable among them in faraid is Zayd Bin Thabit.

Anas Bin Malik reported that Allah’s Messenger (pbuh) said:

<Of my Ummah, the most compassionate toward my Ummah is Abfi Bakr, the firmest in regard to Allah’s commands is ‘Umar, the most true in his haya (Usually translated as “shyness” or “poverty”, it rather means shying away from disobedience and sinning.) is ‘Uthman, the best in reciting Allah’s Book is Ubayy Bin Ka‘b, the best in faraid is Zayd Bin Thabit, and the most knowledgeable about matters of halal and haram is Muath Bin Jabal. Moreover, every nation has a trustworthy one, and the one who is (most) trustworthy of this Ummah is Abu ‘Ubaydah Bin al-Jarrah.>(Recorded by an-Nasa’i, at-Tirmidhi, and others. Verified to be authentic by al-Albani (as-Sahihah no. 1224).)

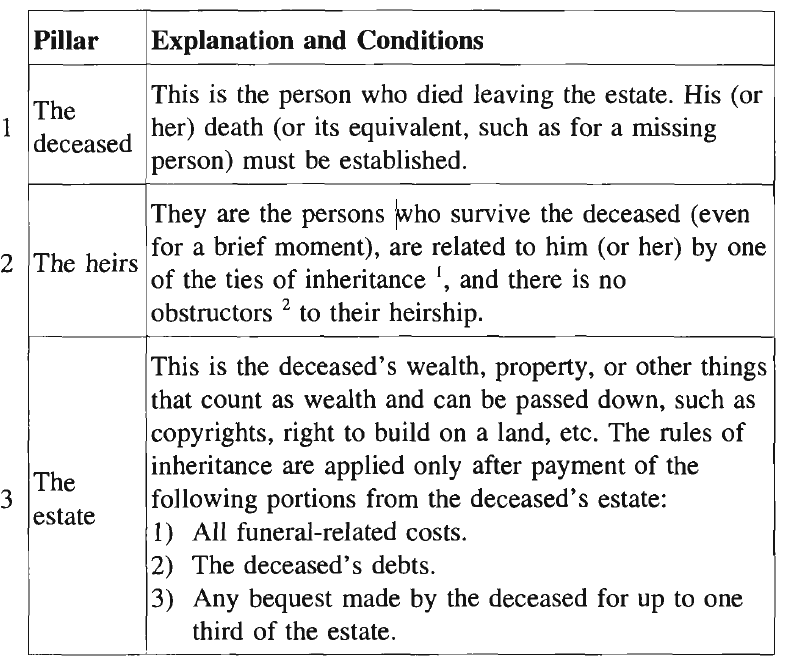

PILLARS AND CONDITIONS FOR INHERITANCE

For inheritance to take place, it must have the following three pillars, together with the corresponding conditions for each:

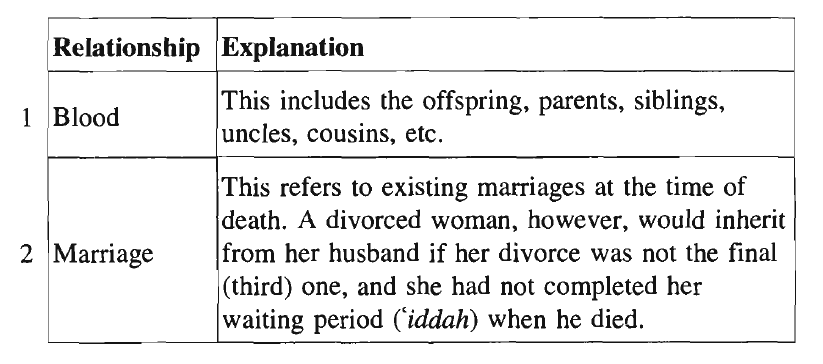

TIES OF INHERITANCE

A person would be a likely heir if he (or she) is related to the deceased by one of the following three types of relationships:

In the next section, we provide details regarding these ties.

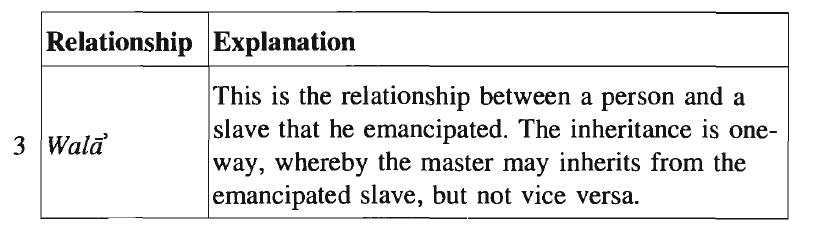

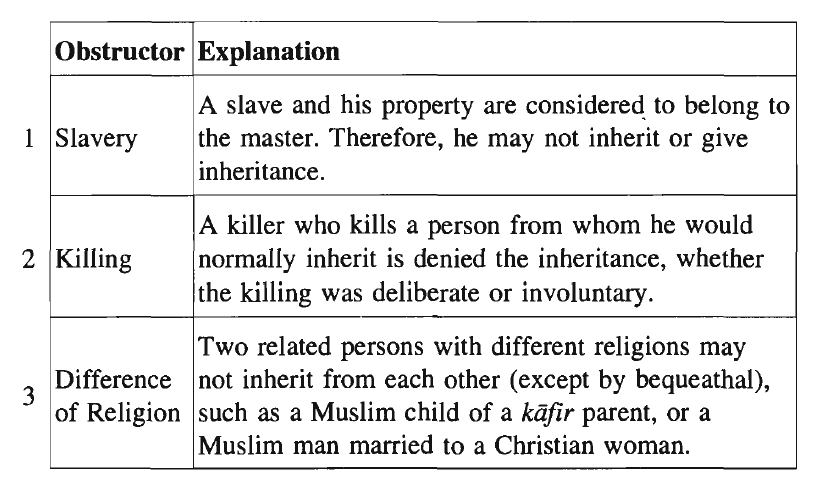

INHERITANCE OBSTRUCTORS

A person who would normally be an heir is denied heirship in any of the following situations:

The Heirs

In what follows we mention the different relatives, men and women, who may inherit from a deceased.

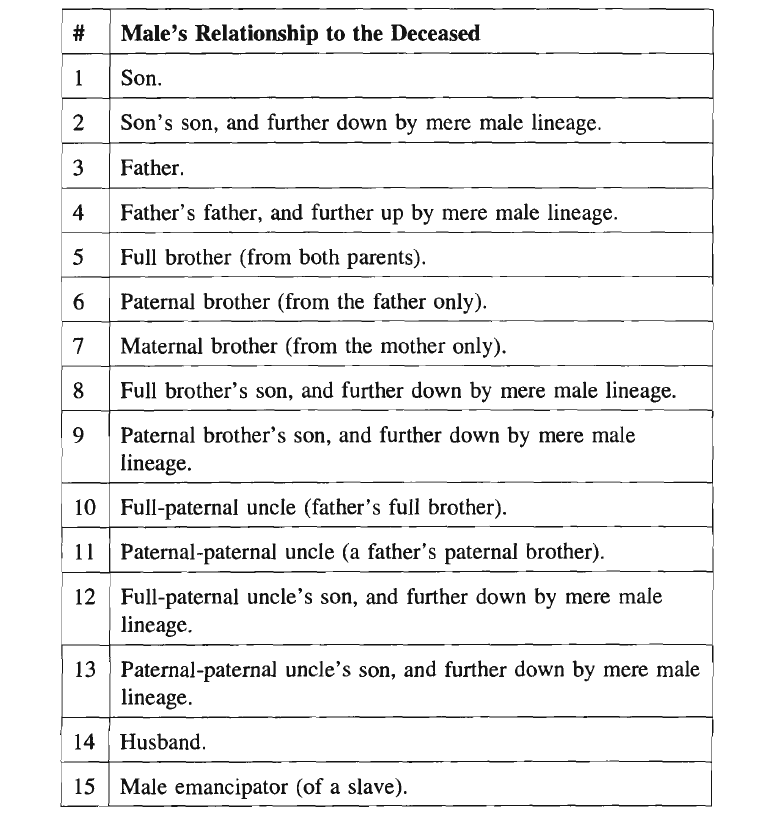

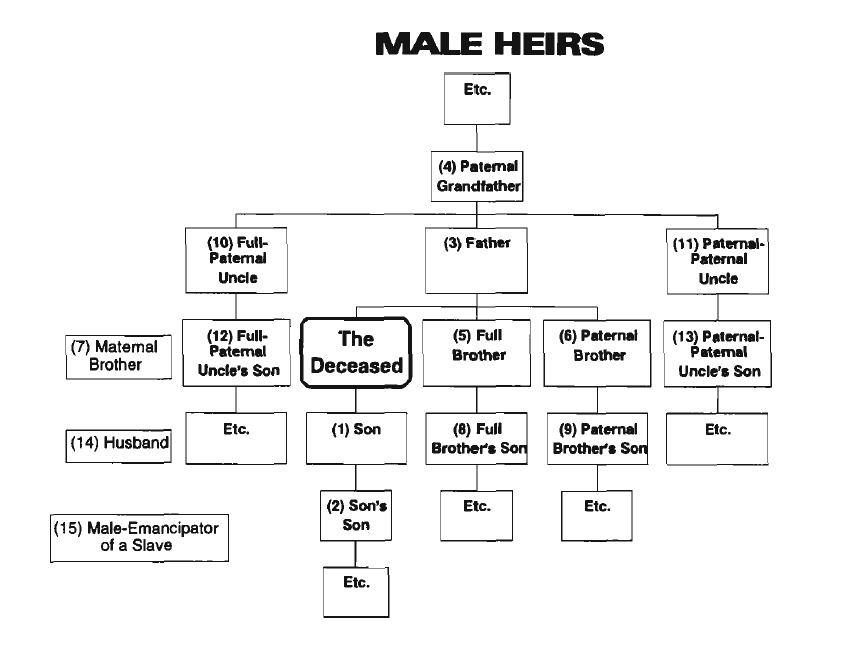

Male Heirs

The possible male heirs are fifteen relatives as follows (review the chart below):

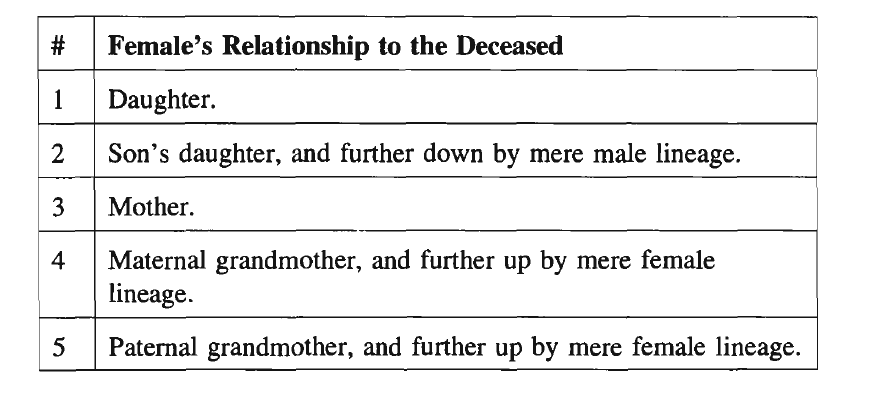

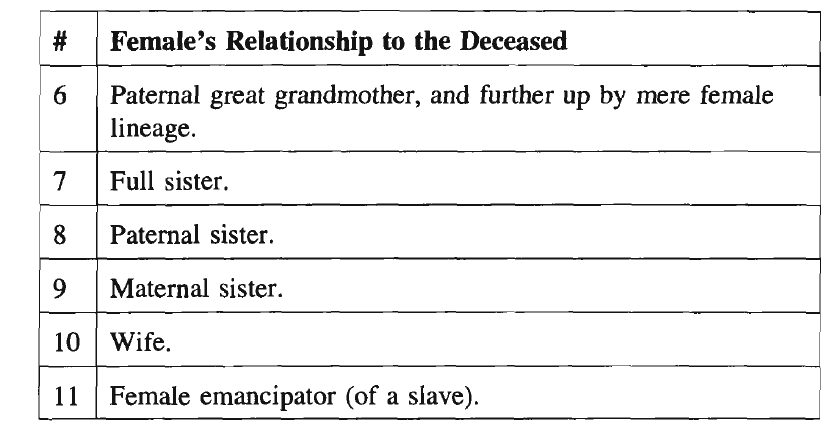

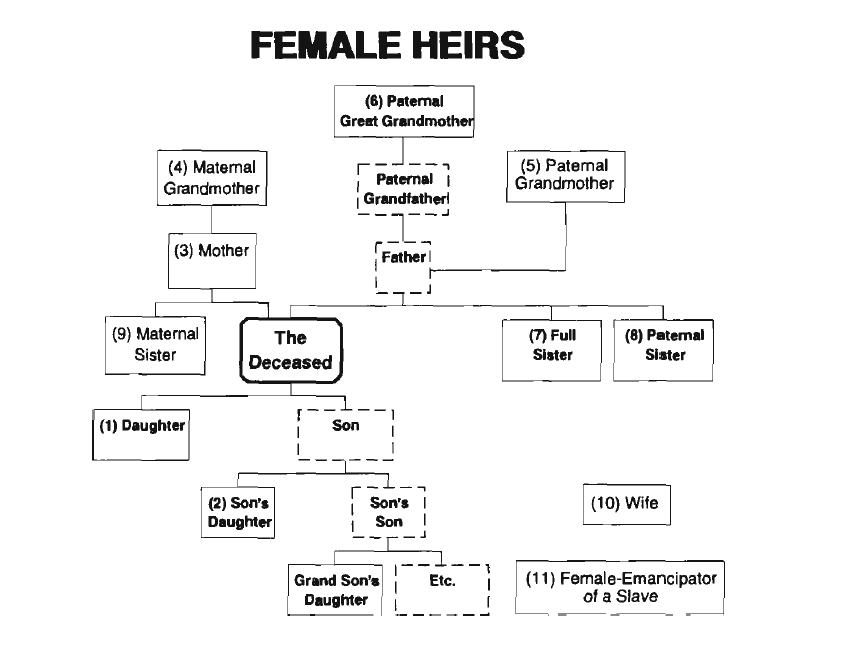

FEMALE HEIRS

The possible female heirs are eleven relatives as follows (review the chart below):

It is important to note that, in the case of female heirs, the inheritance stops at them and does not move on to their children as in the case of male heirs.

TYPES OF HEIRS

Heirs are classified, in accordance with their relationship to the deceased, into three types:

1. Branch Heirs. The branch (or stirps) heirs (BH) are the deceased’s offspring, their offspring, and so on.

2. Origin Heirs. The origin heirs (OH) are either male (father, grandfather, etc.), or female (mother and grandmothers).

3. The Margins. The margins include the father’s branches (the deceased’s brothers and sisters) and the grandfather’s branches (the deceased’s paternal uncles).

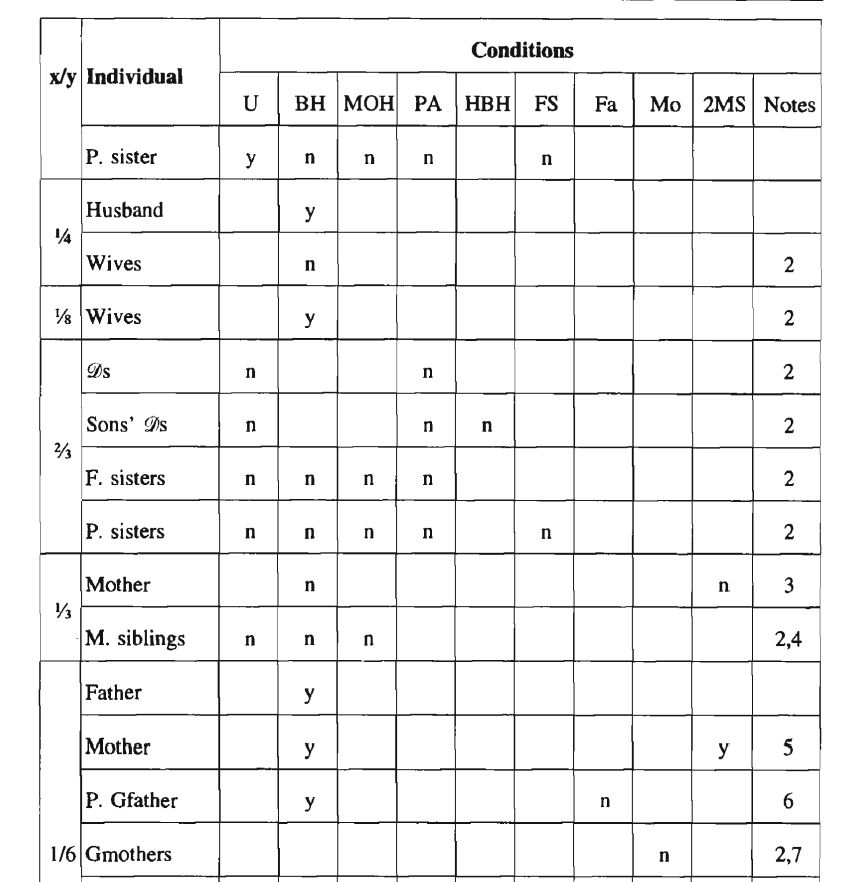

Prescribed Shares

The prescribed shares (furud; singular: fard) are the specific allocations determined in the Quran or Sunnah. They are one-half, one-third, one- fourth, one-sixth, one-eighth, and two-thirds. They hold for various individuals based on the fulfillment of certain conditions. In what follows we describe the situations where these ratios are applicable.

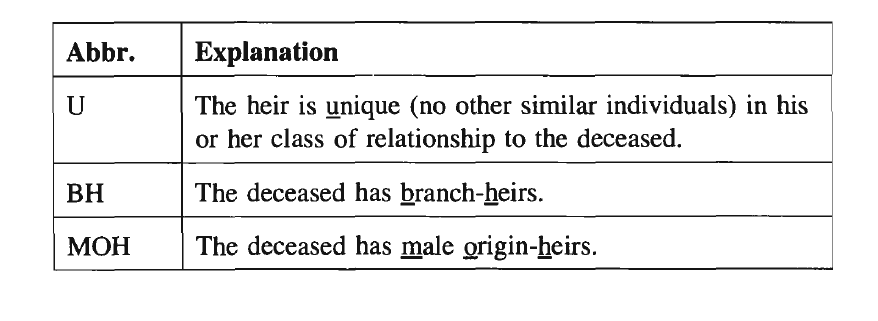

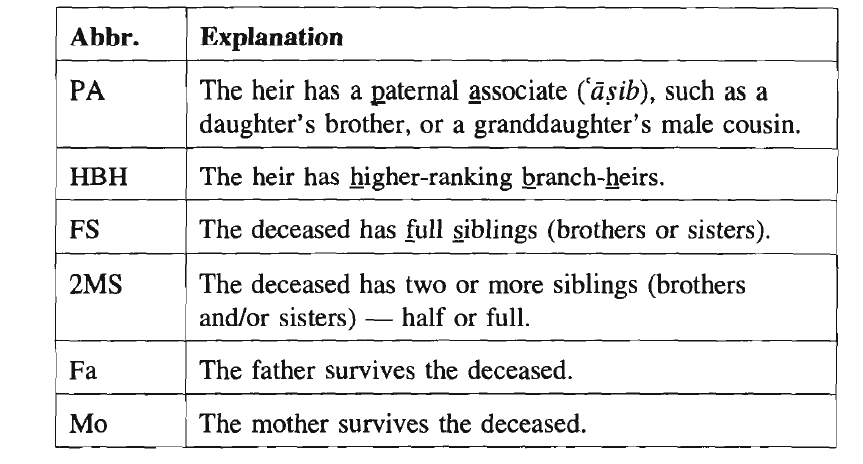

Abbreviations

For the sake of reducing the size of the share-table below, and to limit repetitious terms, we define the following abbreviations:

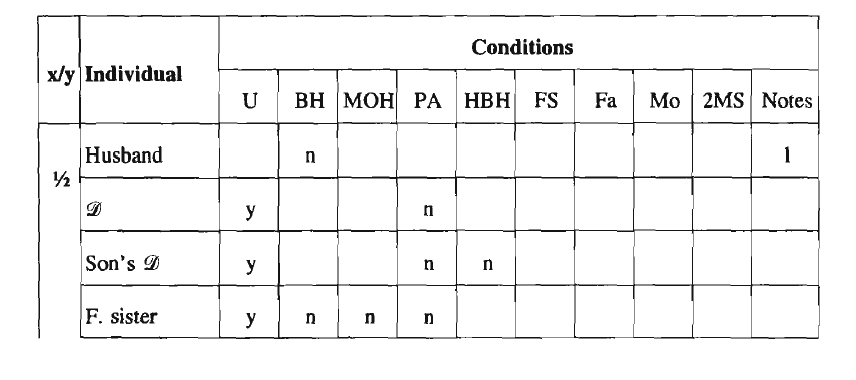

TABLE OF SHARES

In the following table, we use the abbreviations from the previous subsection. In order for an individual to receive a particular share, the required conditions for him (or her) are marked with “y” (yes) or “n” (no). Ex., for a daughter to receive Vi of the estate, U and not(PA) must hold, which means that she should be the only daughter, and she should not have any brothers to cause tasib.

All of the conditions marked for a specific individual must hold simultaneously. The only exception is when the mother receives 1/6, as indicated in the following sub-section. Additional non-common conditions for some individuals are also indicated after the table.

NOTES AND ADDITIONAL CONDITIONS

1. The only case that there would be more than one Q/i) share is for a husband with one sister.

2. The share for 2 or more of the same class (wives, daughters, etc.) is equally divided among them.

3. A special case is when, in addition to the mother, the deceased is survived by a father and a spouse. In such cases the mother receives V3 of the remainder. This case will be discussed in detail later.

4. Maternal siblings have the following specific properties:

1) Both their males and females receive equal shares of the 16.

2) They cause their mother’s share to drop from Vz to 1/6.

5. Only one of the two conditions must hold for the mother to receive 1/6.

6. A grandfather may be an heir provided that there is no female link between him and the deceased. Thus, a mother’s father, for example, cannot be an heir. The mother of such a grandfather cannot be an heir either.

The scholars have two different opinions regarding the grandfather’s share:

a) He takes the position of the father in his absence. In such a case, he would cut off heirship of the deceased’s full and paternal siblings. This is the opinion that we accept.

b) The grandfather shares with the deceased’s full and paternal siblings.

7. Also, there should not be a nearer grandmother surviving the deceased.

8. Also, one of the heirs must be a higher daughter or son’s daughter inheriting 1/2. The reason for this is that, in the absence of brothers, a deceased’s daughters receive % of the estate. If, however, the deceased had left only one daughter in addition to sons’ daughters — all without ‘asibs (brothers), the daughter receives 1/2, and the granddaughters share 1/6, so that the total would be ⅔.

9. Also, one of the heirs must be a full sister inheriting Vi. This is similar to the previous case.

Ta’sib

Inheritance reaches an heir via two routes, fard (prescription) or ta’sib. The ta’sib’s portion of the inheritance has no prescribed ratio. It could be large, small, or even null — depending on the fard amounts (see previous section).

Ta’sTb derives from ‘usbah, which means “clan; paternal relations; agnates”. An individual inheriting through ta’sib is called ‘asib.

Thus, ‘usbah arises from kinship relationships. This has three forms: independent ‘usbah, ‘usbah by association, and ‘usbah by joining with others. These forms of ‘usbah are explained in the following subsections.

INDEPENDENT USBAH

Independent ‘usbah applies to all of the male heirs that were mentioned earlier, except for the husband and maternal brother.

An independent ‘asib may have one of the following situations:

1) If he is alone, he receives all of the estate. Ex., if a deceased is only survived by a son, he takes everything.

2) If there are individuals with prescribed shares, they receive their shares, and he receives anything left after that (see the hadith of Ibn ‘Abbas (t$s>) last chapter). Ex., a man dies leaving a wife and a son. The wife receives Vs by “prescription”, and the son receives the rest by “ta’sib”.

3) If the prescribed shares cover all of the estate, the ‘asib drops from heirship. Ex., a woman dies leaving a husband, mother, maternal brother, and paternal uncle. The husband receives xh, the mother lA, and the maternal brother 1/6. This covers all of the estate, causing the paternal uncle to drop from heirship. There are exceptions to this rule:

a) The sons may not be overruled by the prescribed shares.

b) The father and grandfather turn from ta sib to prescription.

The one of them who inherits would then receive 1/6.

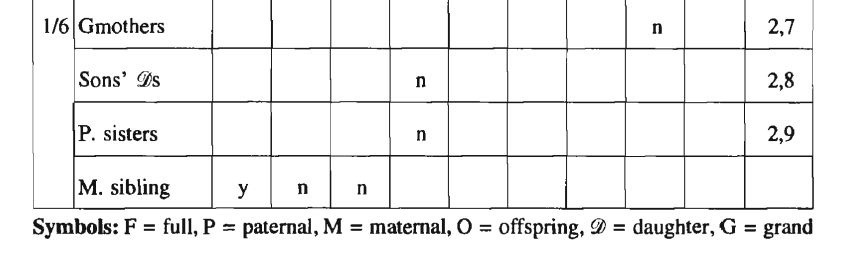

RANKS OF INDEPENDENT TASIB

There are five ranks of independent tasib:

Rule: The existence of a asib of a higher rank cuts off the heirship for those of lower ranks. This is called “hajb”. Ex., a father cuts off the uncle, and a son cuts off the brother.

Thus in a particular inheritance case, it is not permissible to have more than one ‘asib or a team of ‘asibs (‘asib of the same rank).

The only exception to this rule is the second rank. If there is a son for the deceased, he causes the father or grandfather to turn from tasib to prescription, receiving a share of 1/6.

Rule: If there are different ‘asibs of the same rank, the one of closer kinship to the deceased cuts off the others. Ex., a paternal brother cuts off a full brother’s son.

Rule: If there are different ‘asibs of the same rank and same closeness to the deceased, the one of stronger relationship cuts off the others. Ex., a full brother cuts off a paternal brother.

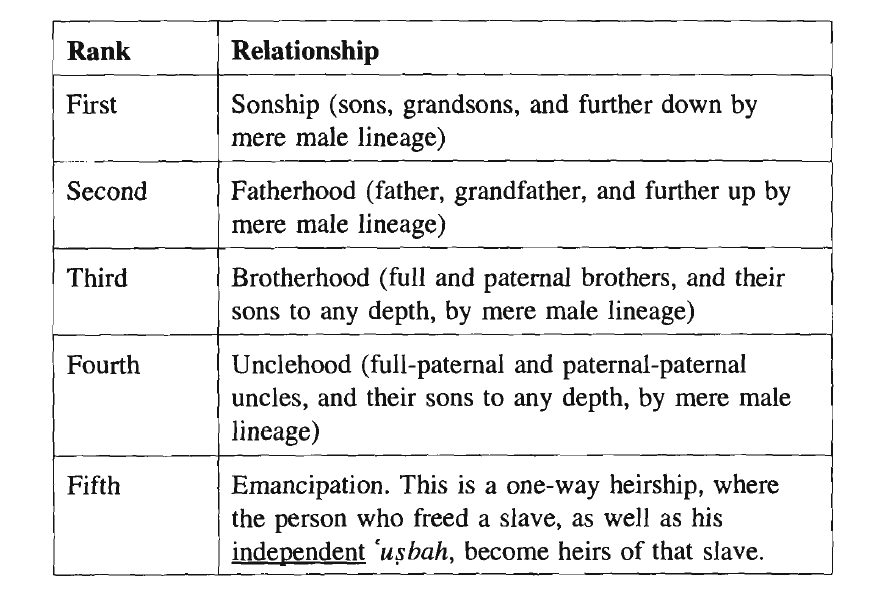

TASIB BY ASSOCIATION

This form of tasib applies to female individuals as follows:

In the above cases, the shares are divided such that a male receives twice as much as a female. Thus, the females turn from being heirs by prescription to being heirs by tasib.

It should be noted that the males affecting this transformation for the female heirs maintain their positions of independent ta’sib, with its rules as presented in the previous sub-section.

Ex., a man leaves a full brother, a paternal brother, and two paternal sisters. The paternal siblings do not receive anything because of the stronger relationship of the full brother to the deceased.

Ex., a man leaves a father, full brother, and three full sisters. The siblings do not receive anything because of the father’s higher ranking.

JOINT TASIB

Joint tasib has two forms:

1) A full sister with daughters and/or sons’ daughters. Ex., a man leaves a daughter and two full sisters. The daughter receives her prescribed 1/2, and the two sisters divide the rest by ta’sib.

2) A paternal sister with daughters and/or son’s daughters. Ex., a man leaves two daughters and a paternal sister. The daughters receive their prescribed 2h, and the sister receives the rest by ta’sib.

It should be noted that the daughters or sons’ daughters receive their prescriptions regardless of the presence of sisters.

Also, when a full sister has joint ta’sib, she would cut off anyone who would otherwise be cut off by a full brother. The same is true in regard to paternal siblings.

Hajb

Hajb is a process whereby a person is cut off heirship — either entirely or partially. It derives from hajaba, meaning veiled or screened.

TOTAL HAJB

Total hajb occurs when the existence of some individuals entirely cuts off others from heirship. Ex., one dies leaving a father and full brother. The father’s existence entirely cuts off the brother from heirship.

Total hajb is applicable to all heirs except the parents, immediate offspring, and spouses.

PARTIAL HAJB

Partial hajb occurs when the existence of some individuals reduces the shares of others in the inheritance. Partial hajb is applicable to all heirs without exception.

Ex., when one dies leaving a wife and a son. The wife’s share is reduced from V4 to Vs because of the son.

Ex., when one dies leaving only one son, he takes the entire estate. But if he left two sons, they would divide the estate in half, reducing the share of either one.

Calculating the Shares

There are some practical procedures that need to be established before one can preform complex calculations of inheritance. In this section, we address the most important of them.

CASE WINDOW

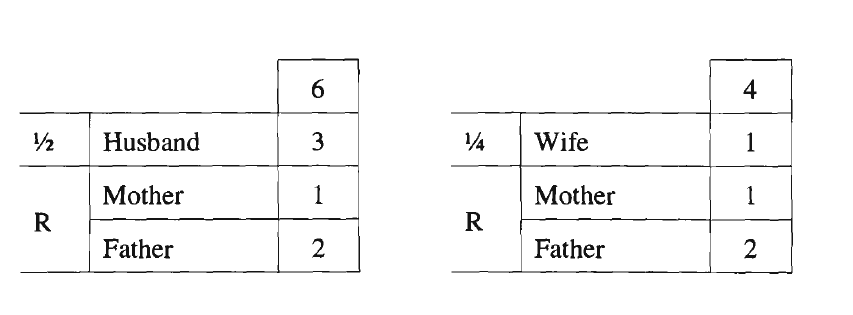

It is conventional to represent an inheritance case in a “window” as follows:

The individual heirs are listed in the central column, their proportions of the estate are listed in the left column. The right column lists the shares, which are the full numbers corresponding to the fractional portions. The box at the top provides the total of the individual shares, which is conventionally called “the base” of the case.

Conventionally, the left column is totally eliminated and replaced by the right one. But we will normally include it in this book for additional clarity.

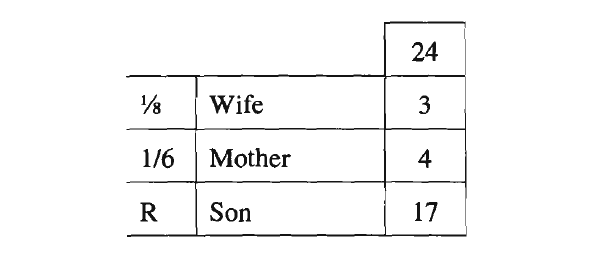

Ex., a man dies leaving a wife, mother, and son. The case’s window is as follows:

This means that the estate is divided into 24 equal shares, giving the son 17 shares, the mother 4, and the wife 3.

INCREASING THE BASE

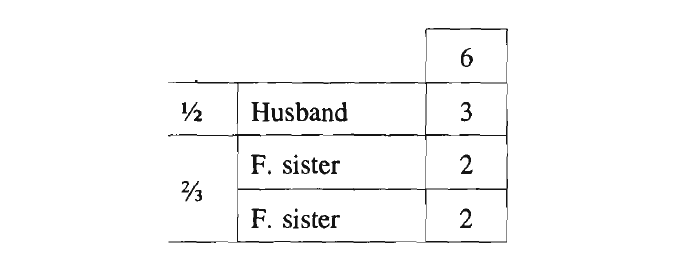

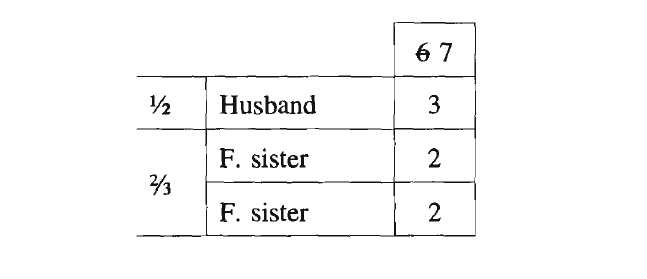

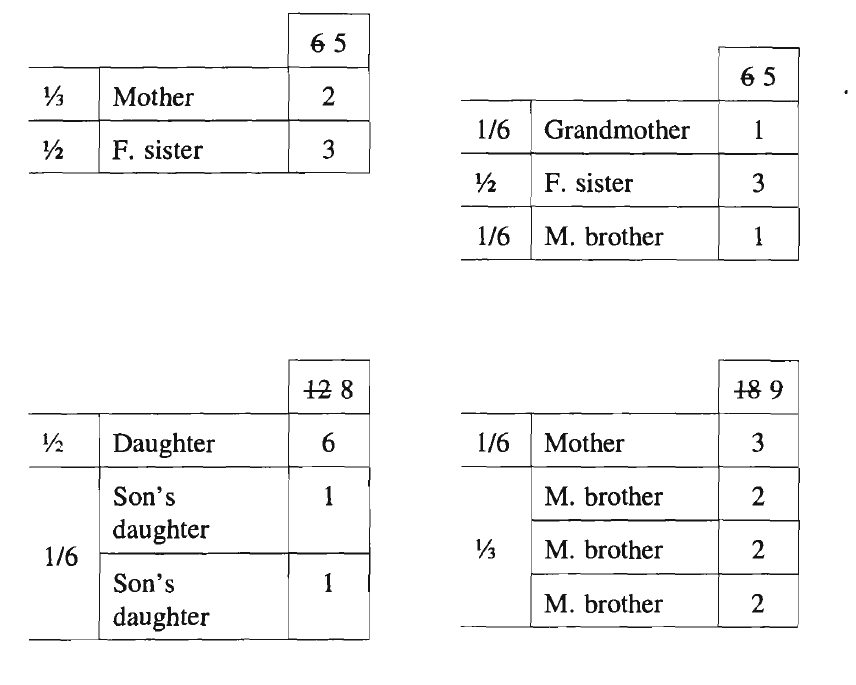

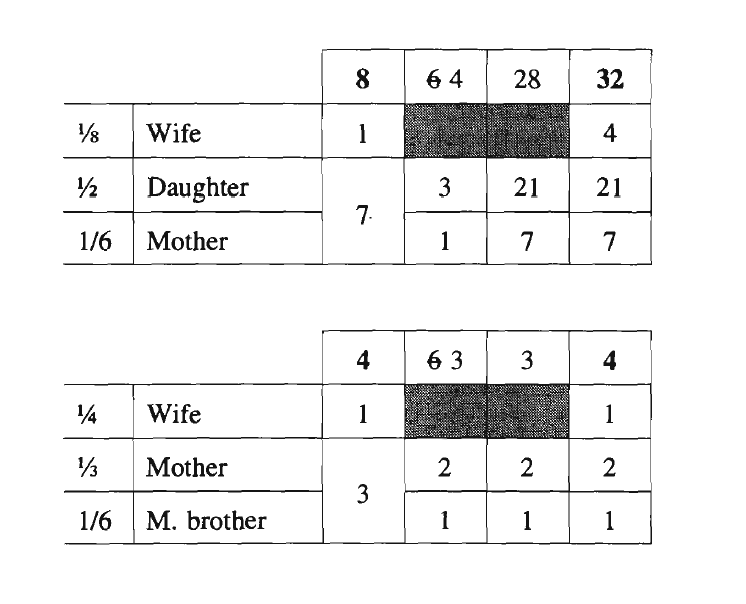

Increasing the base, conventionally called awais required in cases where the total number of shares is more than the base. This can only happen when all of the heirs inherit by prescription. The base is then increased to reflect the correct total. Ex., a woman dies leaving a husband and two full sisters. The case’s window is as follows:

Thus, the total fractional shares (1/2+ 2/3=7/6) are larger than 1, and the shares (3+2+2=7) are larger than the base (6). So, the base is changed to correct for this discrepancy, and the window is presented with the original base “strike out” and replaced by the new base as follows:

Special Cases

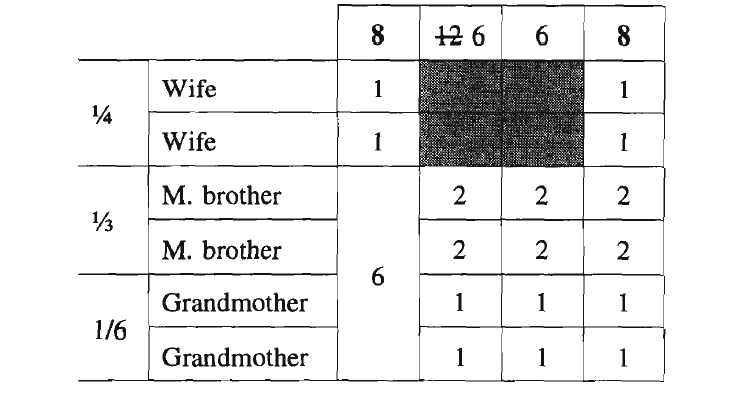

THE TWO CASES OF UMAR

These are two special inheritance cases that have been briefly referenced earlier. Solving them in the conventional way seems to result in a contradiction. They are as follows:

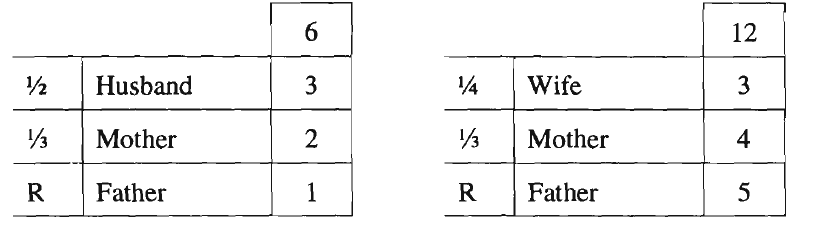

This shows that in the first case, the mother receives twice as much as the father, and in the other she receives slightly less. This is in conflict with the general rule of inheritance stating that if there is a male and a female from the same rank, the male receives twice as much as the female. Because of this, ‘Umar chose to give the mother xh of the remainder after giving the spouses their shares. His opinion was approved by the sahabah and most of the ‘ulama after them.

Thus, the above two cases become as follows:

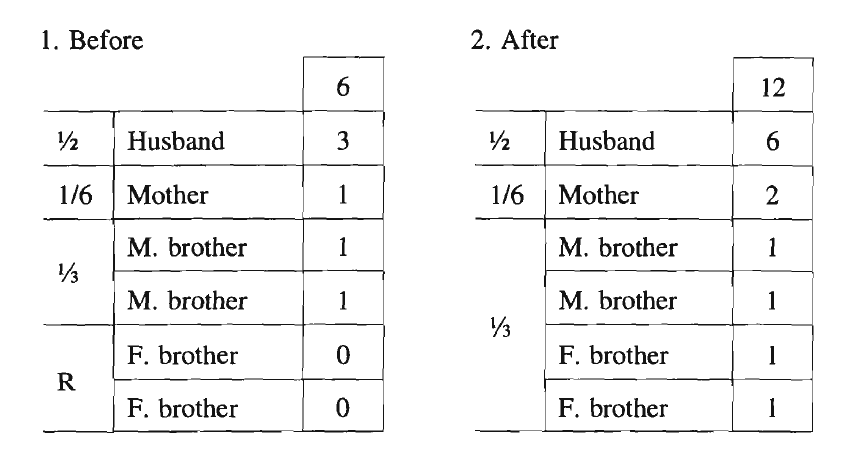

MATERNAL BROTHERS CUTTING-OFF FULL BROTHERS

This case applies when the deceased’s survivors are a husband, a mother, two or more maternal brothers, and any number of full brothers. The normal rules of inheritance result in cutting off the full brothers, while giving lA to the maternal brothers (left table)!

That appears to be unfair. The full brothers are the same as the maternal brothers in that they all have the same mother. In addition, the full brothers are closer to the deceased in that they share with her the same father as well. Because of this, ‘Umar and many other scholars after him have agreed in this case to treat the full brothers as maternal brothers, so that they all share xh of the estate (right table).

GRANDFATHER WITH SIBLINGS

If the deceased is survived by a paternal grandfather and siblings (paternal or full), the scholars (from the sahabah and after) differ into two opinions in regard to the grandfather’s share:

a) The first opinion is to treat him exactly as the father, in which case he would cut off the siblings.

b) The second opinion is that, after giving any prescribed shares, the grandfather receives the maximum of: 1/3 or the remainder, equal share as the brothers, or 1/6 of the total estate.

We adopt the first opinion, which was taken by Abu Bakr (In ilam ul-Muwaqqi’in, Ibn ul-Qayyim mentions twenty different reasons for favoring the first opinion.) in the presence of all of the sahabah — without any objection from them.

The second is the opinion of ‘Umar and others among the sahabah. It leads to many complications that we will not discuss.

Second Distribution

Second distribution, or radd, is opposite to ‘awal. It occurs if the total prescribed shares are less than the full estate, leading to extra shares without heirs. Those extra shares are redistributed among the heirs by reducing the base of the case to the total of the original shares. There are two conditions for radd:

a) The prescribed shares do not cover the full estate.

b) No ‘asib is available to receive the residual estate.

Whereas radd can apply to anyone with a prescribed share, most of the scholars exclude the spouses, so that when the second distribution is made, the spouses maintain their original shares.

In the following, we will look at examples in the absence and presence of a spouse.

1. NO SURVIVING SPOUSE

If the surviving heir is only one person, he takes the whole estate. Ex., if the deceased is only survived by a daughter, she receives half of the estate by prescription, and the other half by radd.

If the survivors are one class, the residual estate is divided equally among them. Ex., if the deceased is survived by two daughters, they receive 2/3 by prescription (1/3 each), and the remaining 1/3 is divided equally among them, so that each one receives a total of 1/2.

If the survivors are of different classes, the individual shares are added up, and the base is replaced by that sum, as in the following examples:

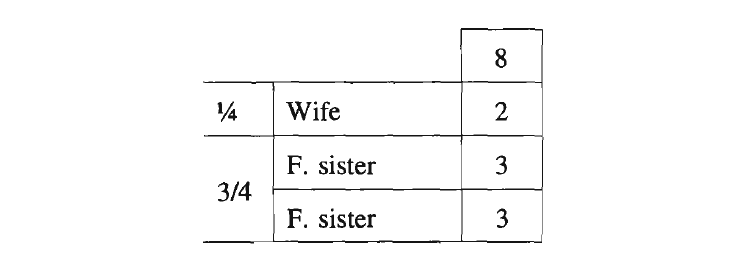

2. THERE IS A SURVIVING SPOUSE

If there is only one surviving heir (or class of heirs) beside the spouse, the spouse’s share is given to the spouse, and the full remainder is given to the other heirs as a combination of fard (prescription) and radd. The following is an example:

Note that the sisters would normally receive 2/3 by prescription, but received an extra (3/4 – 2/3 = 1/12) by radd.

If there are various classes of heirs with the spouse, the problem is divided into four steps (see following examples):

1. In the first step, the spouse is given his or her share, and the remaining shares R are given to the other heirs.

2. In the second step, radd is applied to the other heirs without the spouse.

3. In the third step, the shares of the other heirs after radd are multiplied by the remaining shares R, and then rationalized (reduced to the smallest numbers) if possible.

4. Finally, all shares are unified with the proper proportions and included in one column.

SUCCESSIVE DEATHS

MEANING AND PROCEDURE

Successive deaths, or munasakhah, refers to situations where, after one dies, and before dividing the inheritance, one (or more) of the heirs dies. The procedure for solving an inheritance problem for such cases is as follows:

1. The problem regarding the first deceased (D1) is solved.

2. The problem regarding the second deceased (D2) is solved.

3. The share of (D2) from the estate of (D1) is determined.

4. The shares of the heirs of (D2) are then proportionally calculated from the estate of (D1).

EXAMPLE

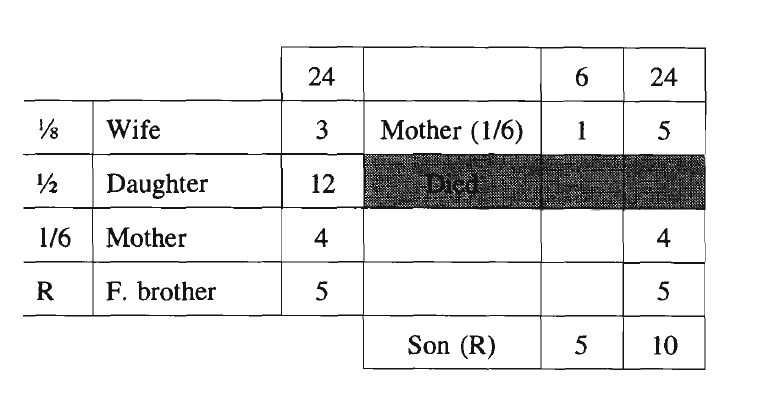

A man died leaving a wife, a daughter, a mother, and a full brother. Before dividing the inheritance, the daughter died leaving a son, in addition to the relatives left by her father. The solution to this problem is presented in the following table:

The first column shows the shares of the heirs from the first deceased (base 24). The second column shows the heirs of the second deceased (mother and son). The third column shows the shares of the heirs from the second deceased. The last column presents all shares relative to the first deceased’s estate.

The munasakhat cases can get very complicated, and the books of faraid usually deal with them in depth and treat various special cases. All of that is beyond the scope of this book, and we feel that the above summary gives an adequate overview of this subject.

SIMULTANEOUS DEATHS

There are situations where two or more persons, who would normally inherit from each other, die together in an accident, such as a fire, drowning, explosion, and so on.

In such cases, if it is possible to determine the sequence of death, the problem reduces to that of successive deaths discussed above.

If it is not possible to determine the sequence, they would not inherit from each other.

Inheritance of a Fetus

CONDITIONS FOR A FETUS’S HEIRSHIP

When a person passes away, if the following conditions hold:

a) It is established that an embryo or a fetus exists in the womb of a woman related to the deceased,

b) The fetus’s relationship to the deceased makes it a potential heir,

c) And the fetus is subsequently bom alive,

This fetus is then a legal heir to the deceased.

In such cases it would be best to delay dividing the estate until after the fetus is delivered, because that would eliminate possible mistakes and doubts in regard to the division. However, if the other heirs insist on dividing the estate, the division may be done while reserving the maximum possible share that the fetus may possibly receive.

POSSIBILITIES FOR THE FETUS

There are many possibilities for the fetus. A number of these may be eliminated in some pregnancies by applying modern technological methods, such as ultrasonic scanning.

The major possibilities are the following:

1. The fetus is born dead (D).

2. The fetus is born a living male (M).

3. The fetus is born a living female (F).

4. The fetus is born a living male/male twin (MM).

5. The fetus is born a living male/female twin (MF).

6. The fetus is born a living female/female twin (FF).

Other possibilities are rare and need not be considered.

POSSIBILITIES FOR THE OTHER HEIRS

In the presence of a fetus, the other heirs could be three types:

1. Heirs whose share is not affected by the outcome of the pregnancy. These heirs are given their full share.

2. Heirs who would drop out from heirship under some outcomes of the pregnancy. Those cannot receive anything before delivery.

3. Heirs whose share would vary depending on the outcome of the pregnancy. Those are given the minimum possible share. If, after the delivery, it is found that they deserved a higher share, the difference would then be given to them.

EXAMPLE

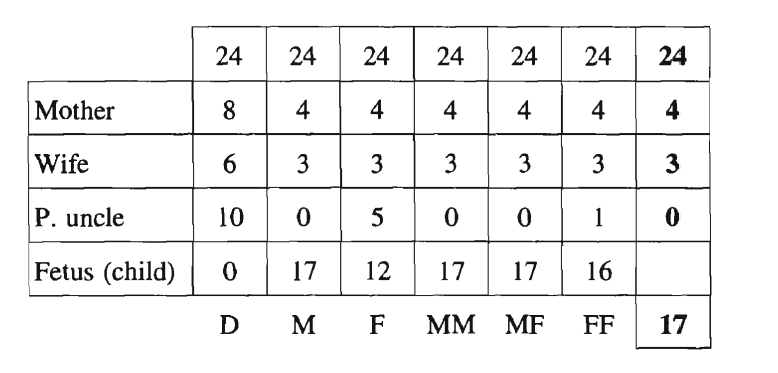

Let us take the example of a man who dies leaving a mother, a pregnant wife, and a paternal uncle. The various possibilities for the heirs’ shares are presented in the following window:

This shows that, out of 24, the mother’s possible shares are (8, 4), the wife’s possible shares are (6, 3), and the uncle’s possible shares are (10, 5, 1, 0). By giving each of these three individuals the minimum possible share, 17 of 24 shares will be reserved until the fetus is bom (right column).

Note that the computations may be simplified by considering just two possibilities for the fetus: FF and MM, because they allow it the highest share.

Missing Persons

Definition

In the subject of inheritance, a missing person is a person who has disappeared for an extended period of time, so that it is not known whether he is dead or alive.

The scholars differ as to what period of time should be allowed before deciding that a missing person is dead. The most reasonable view is that no general rule can be set, but a Muslim judge should decide on individual cases. Matters taken into consideration when making such a decision are the age of the missing person, the circumstances of his disappearance, the land in which he disappeared, and so on.

INHERITANCE OF A MISSING PERSON

A missing person’s estate may not be divided among the heirs until it is known for sure that he is dead, or until the judge issues a decree considering him dead.

A MISSING HEIR

If the missing person is an heir of a deceased, the same conditions should be applied as in the previous case in order to consider him dead. If the judge sets a certain waiting period before such a consideration, the division of the estate should be postponed until that period passes.

If, during the waiting period, the other heirs demand division of the estate, a maximum possible share should be reserved for the missing person as in the case of pregnancy.

Hermaphrodites

Hermaphrodites are individuals who have both male and female sexual organs, or an organ that resembles neither.

In some cases, one of a hermaphrodite’s organs will be ineffective, allowing the other organ to determine its gender. Other behavioral and medical considerations could also determine the stronger of the two genders. In terms of inheritance, the hermaphrodite is then considered to be of the stronger gender.

In cases where it is impossible to specify a hermaphrodite’s gender, its share is then halfway between a male’s and a female’s.

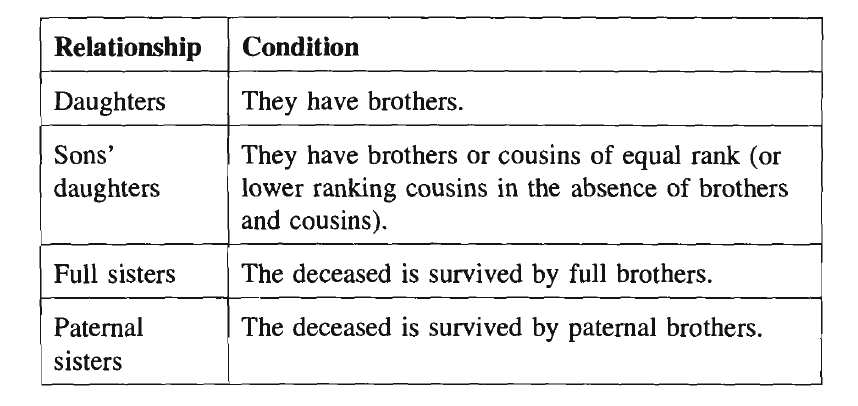

Relatives Through Female Lineage

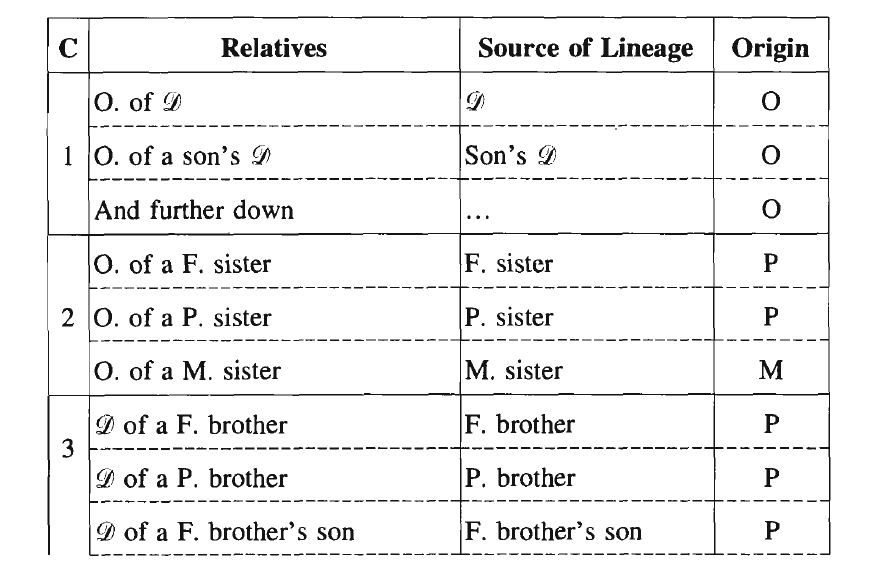

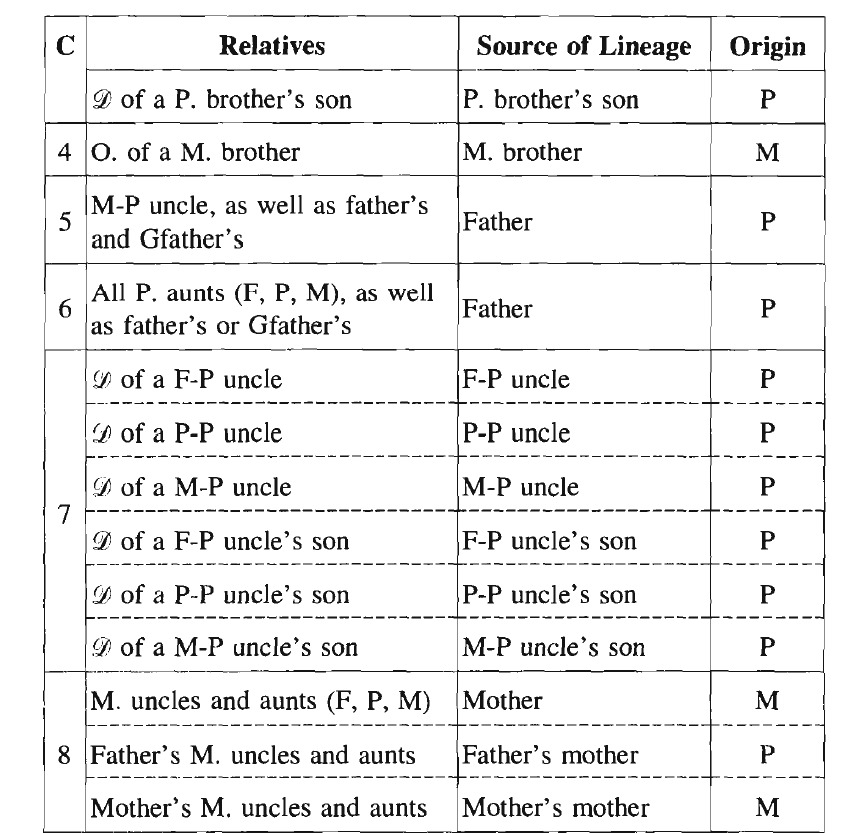

DEFINITION

Relatives through female lineage (thaw ul-arham) are the relatives whose relationship to the deceased occurs through one or more female links, and who do not normally inherit from a deceased — neither by prescription nor by taslb. They are eleven classes as follows:

INHERITANCE

The relatives through female lineage would inherit from a deceased only if he left neither ‘usbah nor prescription heirs (other than the spouses).

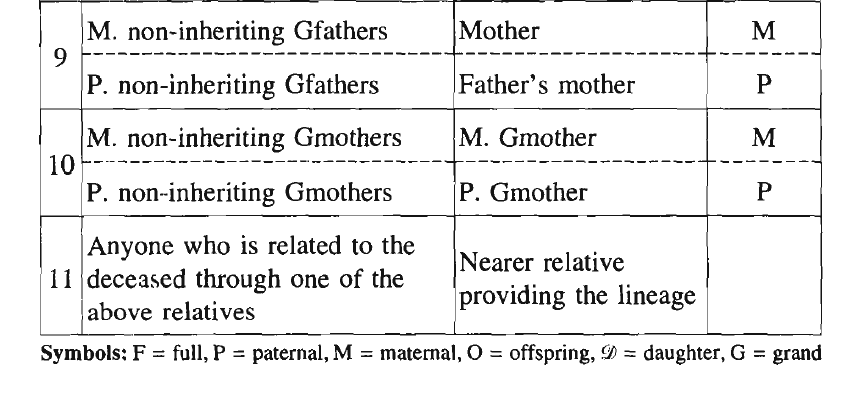

The scholars differ in regard to the order of inheritance of the above relatives. The opinion that we choose is that an existing maternal relative substitutes for the relative who was his or her link to the deceased.

For example, a full or paternal sister’s offspring are related to the deceased, through their mother (the deceased’s sister), through her father, who is the deceased’s father. Thus we say that their relationship is through paternal lineage. On the other hand, the maternal uncles and aunts are related to the deceased through maternal lineage. As for the deceased’s grandchildren, they are related to him through his children. Thus, theirs is an offspring lineage. All of this is provided in the “Origin” column of the above table.

The following rules should be applied in determining the inheritance of those relatives:

1. If there is only one relative, he or she takes the whole estate.

2. For relatives from the same origin, those who are nearer to the deceased or of stronger link to him cut off the further relatives.

3. Maternal uncles and maternal aunts substitute for the mother and receive her share.

4. Maternal-paternal uncles (father’s maternal brothers) and paternal aunts substitute for the father and receive his share.

5. Other relatives from different origins substitute for the relatives through whom they connect to the deceased.

6. Males and females of the same class receive equal shares.

EXAMPLE

A man dies leaving a maternal uncle, two daughters of full sisters, and two daughters of maternal sisters. The solution is as follows:

Comments

John Doe

23/3/2019Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

John Doe

23/3/2019Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

John Doe

23/3/2019Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.