CENTRAL BANKS AND ISLAMIC BANKING

FARAH FADIL

The emergence of Islamic banking in the Middle East and other parts of the Muslim world has brought to the fore the issue of their relationship with regulatory authorities. The importance of this issue is underlined by the world-wide interest in the supervision of banks following the crises faced by the banking industry for the past two decades, and the establishment of stringent rules for regulating traditional banks and their capital.

At the same time, the brief history of Islamic financial institutions has not been crisis-free either BCCI not withstanding, it was in Egypt, for instance, where most of them collapsed with large losses to depositors and larger loss of credibility to the regulatory authorities.

Yet in most of these countries. Islamic financial institutions are effectively outside the control of central banks for the following reasons:

1. From the outset. Islamic banks sought independence from the traditional framework of central bank control, pleading the special nature of their operations, which are in contradiction with existing laws and measures governing the operations of interest-based banks.

2. Though they demand exemption from the constraints of banking supervision and control, they demand the same financial assistance as is given to traditional banks in case of temporary shortages, yet without the payment of interest to the central bank.

3. Ambiguity and lack of understanding, on the part of the central banks, of the principles regulating these banks. Central banks are not well versed in Islamic law and are not trained for it. As a result, these financial institutions have been left to their own devices and regarded by bank regulators as an anathema to the system. In Kuwait, regulation of Islamic banks was left to the Ministry of Finance, a highly unlikely place from which to regulate banks.

4. Relegating the responsibility of regulation to the Ministry of Finance was the outcome of a lack of understanding of how to deal with these banks, as well as the outcome of the debate on whether these institutions should be defined as banks or as non-banks (investment companies).

If they are classified as non-banks, then central banks can be absolved from responsibility for them, and other bodies, such as the Ministry of Finance or the Stock Exchange Authority, can look after them, even if they lack the relevant experience.

It seems, that applying Islamic thinking on the banking industry has raised, once more the issue of justification of state control over banks and provoked hypotheses of whether there is anything special about Islamic banks to warrant their exemption by central banks from their supervision and assistance.

The exemption of Islamic banks from central bank control and its protective umbrella revolves around one central position, namely the denial of a predetermined interest rate on deposits and the lack of sufficient guarantees on their principal.

The foundation and theoretical justification of the existing institutional framework of monetary control does not indicate that prohibition of interest payment has been a cause or a condition for regulating deposit-taking institutions.

In countries, where Islamic banking has been licensed alongside traditional banking, the central bank relationship with interest-free banking has been confused and non-uniform.

The introduction of Islamic banking owes much to the encouragement of some governments in the Arab world and in other Muslim countries. Under the sponsorship of these governments. Islamic banks were established by special legislation (Egypt, Dubai, Sudan, Kuwait & Bahrain) which set them apart from other financial institutions, and from certain provisions of the banking law to facilitate their mission.

Some of these governments went to the extent of participating in the capital of these banks. For instance, the Kuwait government took up 49% of the share capital of the Kuwait Finance House in 1977.

A closer look at the legislation and the manner in which Islamic banks were licensed to work indicates the following:

• The legislation was not designed to grant privileges to Islamic banks as opposed to interest-based banks.

• In the case of the Faisal Islamic Bank, the forerunner of the movement, the legislation reflects the concession granted by the host countries (Egypt, Sudan and Dubai) to a foreign investor Its provisions emphasise the protection of the banks against nationalisation, confiscation and foreign exchange controls with respect to profit repatriation.

Only in 1981 did Islamic banks realise the necessity of involving the central banks in their affairs, when the first expert committee was set up to examine and prepare guidelines on the promotion, regulation and supervision of Islamic banks. Ever since, the relationship between Islamic banks and central banks has not been uniform.

Some began to bring them under supervision, but it was generally with benign neglect, since they were asked to provide data only to the central bank, while others, as in Kuwait, washed their hands of them and referred the Islamic banks to the Ministry of Finance. This divergence reflects the confusion and the background of debate is comprised of two differing arguments.

The proponent of the first view, Ziauddin Ahmed, points to the state of underdevelopment of money and capital markets in Muslim countries, which acts as a severe constraint on the effectiveness of central bank policies in regulating monetary conditions.

Islamic financing offers a golden opportunity, the argument goes, for central banks to introduce new institutions which will deepen the market. At the same time, this is in conformity with the mandate of newly established central banks to play a promotional role in the financial system, including special responsibilities for developing financial institutions and domestic money and capital markets.

A variant of this viewpoint tends to minimise the risks involved in the operations of Islamic banking and the need for central bank control. Depositors in Islamic banks are not guaranteed a fixed rate of return but must also be prepared to share in the losses. The implication is that central banks are under no obligation to protect depositors and that there is no reason why Islamic banks should be subject to strict control by the monetary authority.

In fact, they argue that the risks in Islamic banking are exaggerated and, that there should be less stringent control over Islamic banks as compared to other banks. The profit/loss relationship implies that Islamic banks do not stand as original party to the relationship between depositors and users of funds, but rather perform a proxy (or fiduciary) role for the depositor vis-a-vis the fund user. This proxy ship may take two forms:

1. A delegation of a general nature from depositors to invest in any project, where the profits from this deposit pool are reinvested and finally redistributed among depositors on the basis of a point product system after deduction of management fees.

2. A specific delegation to invest in a particular project after explanation and acceptance of the risk involved. This is called a “specified deposit”, which can also be applied to foreign exchange contracts, where the depositor wishes to take a position in a particular currency or currencies for a certain maturity.

In both the above cases, the bank performs a “fiducial^ function”, where the depositor is aware of the risk. The legal basis for the depositor sharing in the profits of the bank is derived from the agreement of the bank’s shareholders (the only party entitled to the bank’s profits) to surrender part of their profits to depositors. Hence, there is no rationale for imposing supervisory control over Islamic banks.

A corollary of this argument is that Islamic banks, if they need any control at all, need only to be self-regulated by the Sharia. This view is reflected in the deliberation of the secretariat of the Federation of Islamic banks (Al Najar, 1994).

The second and stronger view articulating the relationship between Islamic banks and central banks argues that Islamic banking entails greater risks compared to conventional banks. This has two different implications for central banks’ control. Some argue that because of such higher risks, Islamic banks should be subject to more strict control by central banks.

Others, however, maintain that these higher risks underline the fact that interest-free banking has special and unique properties that are sufficient to disqualify Islamic financial institutions from the status of being a bank, allowing regulatory requirements imposed on other banks to be waived. Exponents of this last view are the influential Bank of England (Pemberton R L, 1984) and the comptroller of the currency of the United States (Sekuta, C, 1988).

Both the Bank of England and the US currency comptroller remove Islamic banks from the realm of central bank control on the following grounds:

• There is no certainty of the rate of return on deposits-owing to the profit-and-losssharing (PLS) principle as well as no certainty of the value of the capital of the depositors. As the ex-governor of the Bank of England stated: “This is of course a perfectly acceptable mode of investment, but it does not fall within the long-established and well-understood definition of what constitutes banking in this country.” In other words, these institutions “cannot hold themselves out to be a bank or to use a banking name”.

• There would be numerous supervisory problems, particularly the difficulty of evaluating the assets of an Islamic bank and assessing the capital adequacy of an institution engaging in essentially capital-uncertain transactions.

• There is also the risk of misleading and confusing the general public by allowing two essentially different banking systems to operate in parallel. In fact, some Arab bankers requested authorities in the UK and USA a special Banking Act or a special section within the Banking Act for Islamic banks, which would mean two sets of rules in the British Banking act. The difficulty is that the Banking Act says that all banks must be treated the same.

In addition to the above, the American supervisory authorities add the need to insulate depositors from risk, while the US banking regulations require insurance from the FDIC before branches of foreign banks may function as banks, i.e., deposit- takers.

Would deposit insurance be acceptable under Islamic principles?

Notwithstanding other factors, it is obvious that the basic objection revolves around the denial of a guaranteed return on deposits and the security of the principal of the deposit. The importance of this view from the prominent supervisory bodies is the great influence it exerts on the official (and non-official) attitudes and responses of supervisors elsewhere, particularly in the Islamic world.

How relevant are these justifications in the context of central banking theory and practice?

Such relevance has to be judged in the context of why central banks are permitted to control the banking industry. More specifically, the issue is whether interest payment on deposits represents a sine qua non for bringing the banking firm under the regulatory authority of the central bank.

But before examining the rationale for central bank control, it is important to identify’ a basic contradiction in the two justifications cited above; deposit safety and guaranteed return on deposits.

Security of deposits is a prerequisite for regulating banks and not to exempt them from regulation. No central banker under any system of supervision can dispute that the primary objective is to protect the individual depositor, and the final aim of supervision is to minimise the risk of any bank sliding into imprudent decisions and practices by its management which may jeopardise the deposit base of the bank. It is clear that one cannot minimise such risks by leaving banks outside the regulatory network set-up by central banks.

Hence it is a contradiction to use the lack of security of deposits as a pretext for excluding Islamic banks from central bank control and supervision.

On the other hand, interest payment (or guaranteed return) on deposits has never been (or would be) a condition or a requirement to impose regulation on banks, nor to leave them unregulated. On the contrary, state control over banks (through central bank regulation) rests on whether non-interest-bearing liabilities at banks or the claims they issue against themselves can be considered as money.

Careful examination of the reasons why the central bank was created as an institution and its history, in practice, indicates that interest payment on deposits is not a requirement for regulating banks.

Can Islamic banks exert influence on economic activities and constitute a potential threat to the price level and financial stability? Do Islamic banks issue claims (deposits) against themselves that meet the criterion of defining banks’ output as money?

In answering the above, the various deposits issued by Islamic banks and their relative importance to the monetary aggregates of the economies in which they operate have to be identified. Islamic banks issue various types of deposits, which are not different from the deposits of traditional banks in terms of their monetary functions.

Demand deposits are issued by Islamic banks in the same way that they are issued by traditional, interest-based banks. They are held to render the normal services of transactional payments, and Islamic banks guarantee to pay these balances on demand. These deposits receive no return, though theoretically, a service charge maybe imposed.

More importantly, they are cheque accounts which can be converted into currency (government dominant money) on demand and at will. In this way, demand deposits with Islamic banks are an integral part of the money supply. But their potential influence on the supply of money and price level will depend on how large they are relative to the aggregate demand deposits in their respective economies.

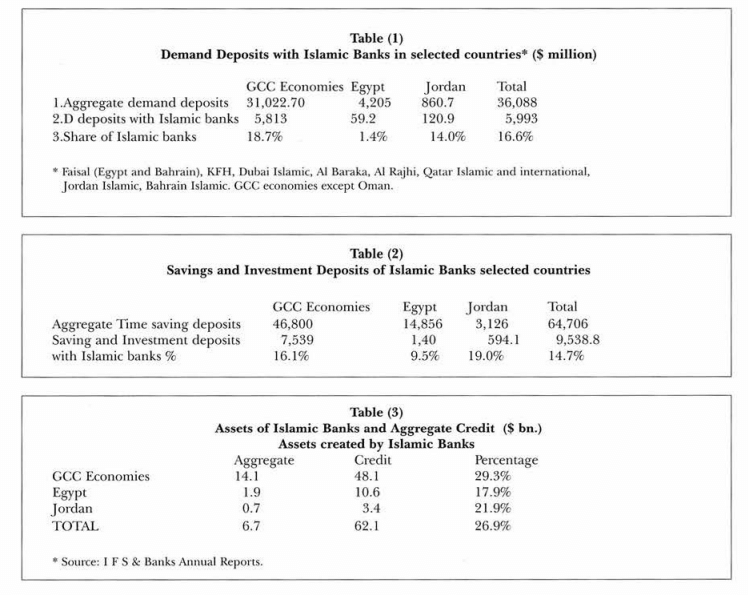

For this purpose, data has been collected from a sample of II Islamic banks working in seven Arab economies (GCC countries plus Egypt and Jordan), for which there is available information for the five financial years (1988- 1993).

The demand deposits of the selected Islamic banks represent an average figure of 17 per cent of the aggregate demand deposits of these economies. These figures may underestimate the relative importance of these banks to the money supply because of the difficulties in obtaining data from some Islamic banks in these countries.

Qatar Islamic Bank, for example, does not publish a balance sheet. The weight of these deposits in the economy-wide aggregate has been reduced because of the low contribution of Islamic banks in Egypt as a result of the difficulties facing them recently.

Nonetheless, an average of 17 per cent is not small and can affect the supply of money in these economies, particularly since demand deposits at these banks achieved a high 8 per cent annual average rate of growth in the past five years.

Savings deposits with Islamic banks earn a return as do their counterparts in traditional banks, except that some Islamic banks pay nothing for these accounts. Because savings deposits receive an annual return at the majority of banks, they are perceived as part investment deposits under the P/L-sharing system. But at the same time, they are also treated as a current account rendering transaction and precautionary service to the holders.

Withdrawals from a savings account are not subject to any restrictions. For instance, the Kuwait Finance House requires a minimum of KD 100 ($300) to be maintained in the savings account to qualify for a profit distribution, but does not put any upper limits on withdrawals.

Effectively, the savings book at Islamic banks can be used in the same way as the cheque book of a current account and for all practical purposes, the savings account is held to provide transaction and precautionary services.

Investment deposits are perceived as being similar to time deposits with a fixed term and constitute the main source of funds for Islamic banks. In fact, this is not the universal case, since some major Islamic banks do not have investment deposits with these characteristics.

Neither Al-Rajhi nor Kuwait Finance House, the largest in the Arab world, have investment deposits as such. The bulk of deposits at Al-Rajhi are classified as current accounts representing 87.4 per cent of the total, while investment deposits of limited and unlimited term at Kuwait Finance House represent only 26 per cent of total customer deposits. The remainder are savings accounts receiving profits, as mentioned above.

It is widely accepted that these investment deposits are utilised on the basis of PLS, where the investment profits (or losses) are shared between the banks and the depositors. Profits are distributed annually, though some banks (Faisal of Egypt) distribute on a quarterly basis.

However, sharing is based on the contribution of investment deposits relative to equity, where shareholders alone bear the administrative cost. A management fee is charged on the profit share of the investment deposits.

Despite the lack of uniformity in treating these deposits, they raise two fundamental issues:

1. Can these investment funds affect aggregate expenditure, and are they sizeable enough to influence the ratio between income and expenditure by households and business, so that they qualify for central bank control?

2. Are depositors in this category equity risk-takers?

Examinations of the data of Islamic banks and their economics will help in attempting to answer the above questions.

Investment deposits with Islamic banks in these countries account for an average of 15 per cent of the total quasi-money of the economies of GCC countries, Egypt and Jordan. Their share in this broader monetary measure might have been higher than 15 per cent if data from all Islamic banks in these countries had been available.

The relevance of these deposits to the debate about central bank control is not only because of their high contribution to quasi-money but also because of the strong and direct link between these investment accounts and aggregate expenditures on consumption and investment goods.

This is implied in the very nature of the utilisation of investment funds on Islamic principles, where trade and real assets must be involved in the disbursement of these funds through Islamic investment instruments, such as Murabaha, Mudaraba and Istisna.

These investment accounts enable Islamic banks to be heavily involved in financing almost all economic activities which are Islamically compatible, e.g., foodstuffs, building materials, cars, real estate and leasing ships and aircraft. Assets created and financed by these deposits with Islamic banks represent around 27 per cent of aggregate credit in their respective economies.

It is obvious that the investment accounts of Islamic banks can exert a relatively strong influence on aggregate economic activities, since altering the nominal stock of these accounts could change the ratio of expenditure to income and allow spending units to cari7 out consumption plans in excess of available income.

This is particularly true in view of Islamic banks’ heavy involvement in instalment finance for consumer durables, for residential housing and other types of expenditure, which practically permit households to consume in excess of current income.

The removal of the interest-rate from the financial system implies that the rate of return on real activities would play the role of allocation in the Islamic financial system. In terms of deposit remuneration, this translates into non-fixed, non-guaranteed rates of return, where the funds raised through investment deposits are invested by the bank on the basis of profit-and-loss-sharing.

Deposit remuneration is related to the profit/loss position of the bank and accordingly they may incur losses as well as earning profits. In this system, savers (depositors in investment accounts) act as entrepreneurs by participating directly in the fortunes of the end user of the funds and therefore share in his risks. These P/L-sharing characteristics are satisfied by Musharaka or Mudaraba.

Examination of the portfolio behaviour of Islamic banks since inception indicates that there is no preference for long-term high-risk (venture capital) Musharaka deals. On the contrary their portfolios are dominated by short-term trade-related Murabaha assets.

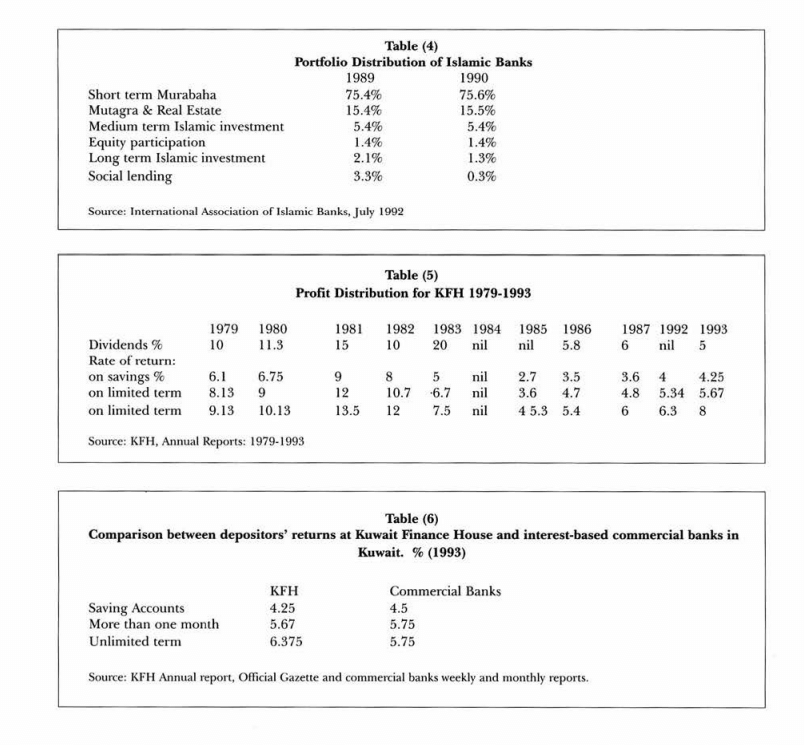

Table 4 shows clearly the short-term (Murabaha) asset concentration of Islamic banks for the period 1989-1990, where these assets account for 75 per cent of their portfolios and equity participation (Musharaka) represented 1.4 per cent.

For 1992/93, accurate data was not available, except for banks in the GCC area, which supplied only aggregate figures on the share of Murabaha in net advances and facilities. Net Islamic investments were in the region of $9.6bn, of which Murabaha transactions represented about $7.8bn, i.e., 81.6 per cent. This increase in short-term Murabaha since 1990 was mainly due to the impact of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

The reasons why Islamic banks selected this instrument, which is not strictly compatible with profit-and-loss-sharing, is beyond the scope of this paper. Nonetheless, the same phenomenon existed in Pakistan and Iran, the two countries which removed all impediments against the application of Sharia law to all aspects of financial transactions.

In this case, the central banks of these countries restricted the high return/high risk asset acquisition by Islamic banks via Musharaka and Mudaraba financing techniques. This led to dominance of low-risk, short-term assets acquired through Murabaha trade financing transactions in the portfolio of Islamic banks in these two countries.

Although non-P/L-sharing instruments dominate the investment policies of Islamic banks, questions remain over whether depositors face higher risks than shareholders in terms of remuneration.

It is argued that Islamic banks tend to leverage their equity position by attracting more investment deposits without creating more risk. If banks are unable to make sufficient profit, they can avoid paying any returns to depositors and if they declare losses, depositors will share in that loss. Therefore, under these conditions the risk to depositors will be higher than those to shareholders of the bank.

It is further argued that the PLS system encourages banks to respond to the economic cycle by reducing investment deposits and increasing equity during the downturn and vice-versa during the upturn, because of their ability to pay less to depositors. This strategy helps in reducing their average cost of funds. Unfortunately, data on profit distributions was only available for Kuwait Finance House for the period 1979-1993, and for Faisal Islamic Bank for 1991-1993.

Table 5: Following the collapse of the Stock Market in 1982, the Kuwait Finance House did not pay dividends for two years (1984-1985), while depositors did not receive returns for one year (1984). In 1992, depositors received between 4 per cent and 6 per cent, while shareholders received nothing in dividends.

Dividend distribution for 1983 was an exception where the bank paid 20 per cent to shareholders out of its reserves. However, the 5-7.5 per cent profit distribution for investment deposits was competitive with the market, given the interest rate structure of the central bank and the non-performing loan portfolio of the commercial banks in Kuwait at that time.

It is noticeable that when profits fell after 1982, dividends were reduced proportionately more than returns to depositors. For 1993, the return to depositors kept pace with dividends (cash distribution) as well as with the interest rates paid on the deposits of commercial banks. See table 6.

While interest rates on dinar deposits were falling during 1993 as a result of the central bank reduction in the discount rate, Kuwait Finance House’s actual remuneration to depositors was in line with the official rate on savings accounts and higher than commercial banks indicative rates to depositors.

As for the Faisal Islamic Bank (Egypt), its published balance sheet (1991-1993) indicates that all net profits available for distribution were given to investment deposit accounts. In fact, dividend distribution was zero and shareholders were given nothing for the 3- year period. Returns on deposits were in line with interest rates paid on the Egyptian pound by commercial banks and the payment of these profits was undertaken on a quarterly basis.

The potential impact of the PLS system on the risk-return profile of depositors has been so far a theoretical possibility. In practice, the portfolios of Islamic banks tend to favour non-PLS Islamic investment instruments. There is no strong evidence to support the potential risk to depositors vis-a-vis shareholders.

The rate of return paid on alternative investments in the non-Islamic sector reflects the financial environment within which they operate. Failure to recognise the impact of this environment would be at the expense of depleting their deposit base.

However, the short-term asset concentration in their portfolio was a response to the absence of the protective cover to the lender of last resort services provided by Central Banks. Islamic banks not only resorted to low-risk Murabaha, but also had to provide for their own emergency liquidity needs by developing their own liquidity management techniques.

Central Bank intervention in the currency business on behalf of the state is based on the need to exclude currency and note issue from free trade in order to protect its value and to prevent financial instability.

Accordingly, individual banks were relieved from the responsibility of each keeping their own reserves. But they did this in the unshaken belief that the central bank was not going to shut its doors in time of emergency. This meant that the monopoly of currency issue was not enough to achieve the goal of financial stability unless the central bank stood ready, at all times, to supply reserves to the banks.

It is the “lender of last resort” function rather than monopoly of currency production, which is the source of its responsibility to the currency. Without this protective service, the stability of banks and the whole financial system is undermined.

However, the “lender of last resort” is not just about rescuing a bank at a time of collapse. It is primarily the ability of a central bank to introduce a high measure of elasticity into the supply of reserves on a daily basis, which is absolutely vital if the central bank is to exercise effective control over amounts of currency and credit in the system.

The lack of such elasticity would reduce the central bank to the equivalent status of other banks, with a limited credit horizon, and undermine the confidence of individual banks in their ability to carry out their operations without worrying about daily liquidity. This is principally why central banks are present in the money market of their currencies on a daily basis, to provide liquidity through a variety of methods, such as the discount window.

Because Islamic banks are deprived of this protective service, it is essential they maintain a highly liquid portfolio, however detrimental to their profitability and their ability to compete. In many countries, they have no access to central bank reserves, though they are required to maintain (compulsorily or voluntarily) part of their reserves with the central bank. Some central banks argue that the facility is available if Islamic banks are willing to pay the cost, i.e., the rate of interest. This is of course unacceptable to Islamic banks.

Since the late seventies. Islamic banks have developed their own techniques for the daily management of liquidity in co-operation with commercial banks. These techniques are based on the concept of interest-free deposit placement/borrowing by Islamic banks, which takes two forms: the point system; and the exchange of deposits.

When using the point system, an Islamic bank places an amount of local currency with a commercial bank for a few days. When the Islamic bank needs liquidity, it may ask the bank to return the favour by lending the Islamic bank an amount of their choice but in the currency and maturity of the choice of the Islamic bank. The amount the bank lends to the Islamic bank is related to the value the bank attaches to the favour of the Islamic bank, which translates into the number of points accumulated for the Islamic bank as a result of the interest-free placements.

These points are calculated on the basis of the total amounts and durations of the interest-free placements made with the bank. It is important, however, to emphasise that neither the total number of points nor the number of points utilised are made available to the Islamic bank. This implies that the conventional bank determines the amount, while the Islamic bank determines the currency and the maturity.

The exchange of deposits is a similar mechanism to the point system, except that it is a back-to-back interest-free deposits-swap and it differs in terms of its longer maturity (1- 3 months). Assuming that an Islamic bank would like to place an interest-free deposit in Kuwait Dinars for one month, in return for dollars (interest-free deposit) for the same maturity, the Islamic bank will seek quotes from a number of banks on the amount of dollars they are willing to lend on an interest-free basis in return for the Kuwaiti Dinar deposit.

The placement of Kuwaiti Dinars will go to the highest bidder in terms of the maximum amount of dollars offered. Commercial banks will calculate how much the interest-free placement is worth to them (in terms of prevailing market interest rates), but Islamic banks will only compare the quoted amounts and choose the highest. At maturity, the transaction is reversed: the Islamic bank receives its Kuwaiti Dinars and the other bank receives its dollars in the original amount.

There is of course, some credit risk, but it is the exchange risk at maturity, which should be considered, particularly since Islamic banks cannot hedge as other banks do. Though the amounts exchanged may be in favour of the Islamic bank, this is not usually the case. These liquidity techniques are symptomatic of the risks faced by Islamic banks in the absence of the central bank protective liquidity services that are available to other banks.

In fact, this absence can lead to a sub-optimal return for Islamic banks, adversely affecting a large number of depositors, and has been intensified by the need for maintaining a higher proportion of their assets in liquid form. The central bank places a short-term investment deposit with the Islamic bank whenever liquidity is required.

These deposits are suitable for central bank purposes, since they carry a known return and are liquid and highly safe because they are short-term, trade-related and supported by first-class guarantees. The Kuwaiti experience in this respect is helpful, as the Central Bank of Kuwait has supported the banking system with deposit placement since the seventies, while a central bank law allows the Ministry of Finance to place deposits in foreign currencies with local banks.

Central banks can deal with the liquidity requirements of Islamic banks through the exchange of deposits. This deposit exchange is quite similar to a “swap” as a money market product which does not require extensive preparation and training by central banks. The Central Bank of Kuwait has been helping local banks to improve their liquidity management through a swap facility as an alternative to the discount window, which underlines its ability to introduce a larger measure of elasticity in the supply of reserves to the banking units.

It is high time that “deposit exchanges” be considered by central banks, since it is Islamically acceptable as well as being problem-free, for it has been practised for over 10 years by Islamic banks in co-operation with conventional commercial banks.

This paper has endeavoured to examine two issues concerning the exclusion of Islamic banks from central bank control and assistance:

1. Absence of guaranteed and predetermined interest payment on Islamic deposits.

2. The Profit-and-loss-sharing system turns the depositor into an equity risk-taker.

An analysis of the foundation of central banking and the rationale for controlling the banking system indicates that interest payment on deposits was neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for regulating banks. That control is founded on one important assumption, namely the inherent instability of money unless put under public control.

It has been shown that there is nothing of significance about Islamic banks which would qualify them to be excluded from central bank control, since their deposits possess the same money properties as deposits of other banks. They are capable of influencing general equilibrium through prices and savings/expenditure decisions, particularly in view of their weight in the national aggregates in their economies.

As for whether depositors are becoming equity risk-takers, it seems that high risk/high return Musharaka transactions do not feature prominently in the portfolios of Islamic banks. From the limited evidence provided. Islamic banks are not heedless risk-takers, since they responded to the restrictions imposed on them by selecting a portfolio dominated by liquid and less risky Islamic investment instruments.

Islamic banks also responded to their exclusion from the central bank protective cover by developing their own liquidity products, which has helped them overcome unexpected reserve pressures, but has exposed them and their depositors to adverse competition in the money market. Leaving Islamic deposit-takers unregulated and outside the protective net of the central bank, is not consistent with its responsibility towards the currency and the maintenance of financial stability.

Islamic liquidity products should be adopted and/or modified by central banks as official instruments for dealing with the reserve shortages of Islamic banks. However, central banks are in need of advice on Islamic finance, either from the Ministries of Religious Affairs or from a special Sharia committee, whose first duty is to ascertain that these banks are conducting their business without the violation of their Articles of Association.

Edited By Asma Siddiqi

Institute Of Islamic Banking And Insurance London

Comments

John Doe

23/3/2019Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

John Doe

23/3/2019Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

John Doe

23/3/2019Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.